[ad_1]

The mainstream assumption is the status quo will continue on much as before. This isn’t just unlikely, it’s impossible if total energy produced and consumed declines.

Correspondent C.A. submitted this insightful interview with economic strategist and historian Russell Napier: “We Will See the Return of Capital Investment on a Massive Scale”.

In Napier’s telling, the 40-year period from 1980 to 2020 was dominated by central banks (monetary policy) and markets (enterprises seeking to maximize profits).

These forces fueled the rise of globalization (maximize profits by arbitraging lower labor and production costs overseas via offshoring production) and financialization (vastly expand debt and leverage but keep debt service low by steadily reducing interest rates).

The second-order effect of the resulting hyper-globalization and hyper-financialization was hyper-dependency on geopolitical rivals and on monetary intervention and credit/asset bubbles to support consumption.

Neither was sustainable. Near-total dependence on geopolitical rivals in service of private-sector profits created existential national security vulnerabilities which must now be addressed by reshoring / homeshoring / friendshoring critical production.

The market, ruled solely by incentives to maximize profits by any means available, created this vulnerability. It is incapable of resolving it.

I covered all these dynamics in depth in my book A (Revolutionary) Grand Strategy for the United States which predated the Ukraine War by four months.

Napier sees governments replacing central banks as the primary force in creating credit and guiding policies / incentives.

He explains that governments don’t have to rely on central banks to create money or credit, or on issuing Treasury bonds that are purchased by investors. Governments are guaranteeing commercial bank loans issued by private-sector banks, in effect expanding credit without creating more government debt.

These guarantees backstop commercial bank loans made in accordance with government directives and goals.

If a borrower defaults, the government will cover the losses so the lender is made whole. It’s riskless lending for banks and keeps the expanding credit off the government balance sheet.

Napier calls this “the politicization of credit.”

Napier explains why inflation will be maintained in a range of 4% to 6% for years to come: inflation is the only way to reduce the debt burden which has reached $300 trillion globally, and about 250% of GDP of many nations. (This is the total of both government and private-sector debt.)

Napier refers to this as “financial repression” because inflation that’s higher than bond yields robs savers and benefits debtors, whose earnings rise with inflation while their debt service remained fixed. (This assumes fixed-rate loans, of course.)

This will also restore the purchasing power of younger workers as wages rise, at the expense of older (and wealthier) generations.

The net result of governments taking control of investment and credit creation “will mean a huge homeshoring or friendshoring boom, capital investment on a massive scale into the reindustrialization of our own economies.”

Governments will have to create enough credit to fund both this massive capital investment (known as CapEx, capital expenditures) and maintain consumption.

Napier points to the 1946-1979 period as an example of governments guiding the economy more than central banks guiding the economy.

All this makes excellent sense, but Napier overlooks three consequential dynamics:

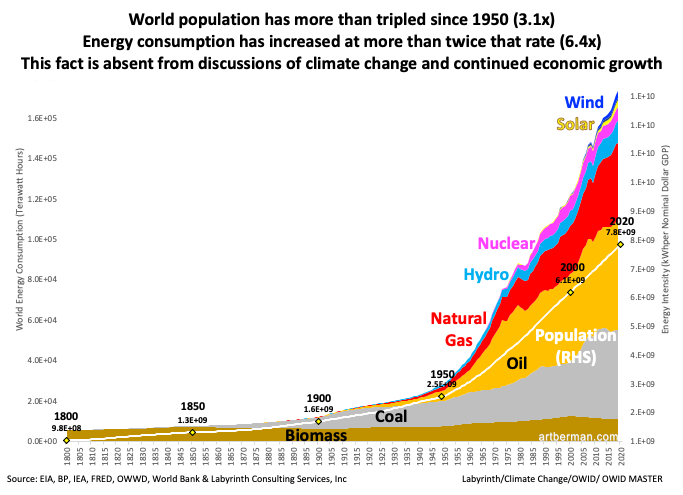

1. The energy cliff, as hydrocarbon production declines faster than new sources can be brought on line to replace them.

2. The demographic cliff as workforces decline and the cohort of retirees to be supported balloons.

3. The impossibility of funding massive new CapEx and infrastructure spending, supporting the ballooning cohort of retirees and consumer spending to keep the “waste is growth / Landfill Economy” humming while keeping inflation tamed to 5%.

In other words, there will be tradeoffs. If you want moderate inflation (politically necessary, as high inflation loses elections) and massive increases in CapEx, consumer spending has to take a hit.

Furthermore, inflation will be driven by two forces: scarcities of essentials like food and energy, which are basically the same thing in industrialized fertilizer-dependent agriculture, and the expansion of credit in excess of increases in productivity.

If $1 invested in CapEx generates more value in terms of goods and services, that means productivity is increasing. If CapEx doesn’t generate more goods and services, productivity is stagnant.

As I’ve explained, this is what happened in the 1970s: massive CapEx was invested in retooling the U.S. industrial base to reduce pollution and improve efficiency.

The reduction in pollution greatly improved well-being but didn’t increase GDP or productivity. We only manage what we measure, and since we don’t measure well-being, the real gains of this CapEx were not even measured.

Like well-being, we don’t measure National Security economically, so improvements in the security of our production of essentials will not even be recognized.

The real gains of homeshoring won’t even be recognized or understood unless we throw out the current methodology of economic measurements and replace it with a modernized set of measurements that aren’t limited to production and consumption (i.e. “growth”.).

As for energy, what most people miss is Jevon’s Paradox: adding sustainable energy (however you define that) doesn’t replace our consumption of hydrocarbons, it simply increases our total consumption of energy.

Another factor most people miss is the scale of the hydrocarbon complex everyone is hoping to replace, and the timeline of that replacement.

Despite decades of investment, alternative energy supplies only 5% or so of global energy. Those pounding the table for nuclear energy rarely mention the timeline for constructing enough plants at scale to make a difference: decades, not years.

Since the cheap-to-get oil has been extracted, what’s left costs more. Yes, technology improves, but physics wins in the end; more energy must be expended to get the hard-to-get oil out of the ground.

These realities dictate an Energy Cliff in which oil production declines faster than new sources can be brought online. And rather than consume more energy as new sources are brought online, we’ll consume less and it will cost more, for all the reasons I explained in my book.

The demographic cliff is equally baked in. The workforce of the next decade can’t be expanded, it’s already here, along with the soaring cohort of retirees.

If sacrifices must be made in consumption due to higher costs of essentials and the need for massive CapEx, the consumer economy will shrink.

Since the system is optimized for expansion, that contraction will upend the entire global economy as it is currently configured.

On top of these three factors, there’s the soaring healthcare costs generated by lifestyle diseases (diabesity, etc.), high levels of pollution in developing nations and the aging populace.

Profiteering doesn’t generate health, and profiteering has been the name of the game so long few can imagine any other way of living.

The mainstream assumption is the status quo will continue on much as before. This isn’t just unlikely, it’s impossible if total energy produced and consumed declines.

As energy analyst Vaclav Smil put it: “I’m not an optimist or a pessimist. I’m a scientist.” Rather than waste time arguing about optimism and pessimism, let’s focus on physics, costs and timelines, i.e. realistic assessments, and on the trade-offs needed to reach our goal of a sustainable, open-to-all, fair economy.

This essay was first published as a weekly Musings Report sent exclusively to subscribers and patrons at the $5/month ($50/year) and higher level. Thank you, patrons and subscribers, for supporting my work and free website.

[ad_2]

Image and article originally from www.investmentwatchblog.com. Read the original article here.