[ad_1]

Your author recently had the opportunity to contemplate whether there is any relationship between today’s global economic circumstances, how they are reported by the financial media, and the mind, body, and spirit of John Blutarsky. The anticipant reader will not be surprised that, indeed, a tortured connection was found.

Bluto, as he was known to his fraternity brothers, is a character in Animal House, a 1978 comedy about the American college campus on the cusp of the countercultural revolution of the 1960s.

Bluto is a frowsy man. Unkempt. Rumpled. Bedraggled. His physical condition could be charitably described as circular. As for intellect, he has little. According to the dean, “Mr. Blutarsky” is “maintaining” a grade point average of “zero point zero.” (Though, to be fair, the dean does not elaborate on the grading scale’s range.) When his fraternity is expelled en masse, Bluto responds: “Christ, seven years of college down the drain.”

But what he lacks in body and mind, Bluto makes up for in spirit. The expulsion galvanized Bluto, and upon the movie’s release, audiences were treated to one of the most rousing speeches in US history — an oration played to this very day in sports stadiums and arenas across the nation. The fiery address gained added sharpness by its contrast with and juxtaposition to a speech given one year later by then–US president Jimmy Carter.

President Carter delivered a prime-time address that, like Bluto’s, sought to rouse the crowd to confront the obstacles that lay before them. In Bluto’s case, the audience was his fraternity brothers, their obstacles institutional in nature — the dean who had expelled them and the more strait-laced and influential fraternity that had conspired against them.

Carter’s audience was the American people, the related challenges economic. The country had been suffering through years of high unemployment, high inflation, gasoline shortages, and a general economic stupor. The official title of the address was “Crisis of Confidence,” but it has since become better known by another name: The Malaise Speech.

It was, as one political commentator put it, “perhaps the most politically tone-deaf speech in modern American history.”

Your author brings all this up because the spirit of the Malaise Speech — and not Bluto’s — has seeped into today’s media analysis of the world economy and by extension the public consciousness.

Though the following focuses on one media outlet’s analysis of a lone month in a single country, it illustrates a broader point. The financial media offers diversions and detours all the while ignoring the obstacle itself: the 150-month malaise in global economic activity.

Ignorance is strength.

How was the US economy performing late last year?

The Economist offered three points on this question as the curtain closed on 2019. The first:

“Official data to be released this morning may show that America’s index of industrial production, a widely watched measure of economic health, fell again. In recent months, weak oil prices have hit mining interests; a strike at General Motors constrained manufacturing output. The trade war with China has hardly helped. President Donald Trump, who wants to give America’s heavy, dirty industries a shot in the arm, may be disappointed with the latest numbers, but, fortunately, such industries only make up a small share of the whole economy.”

What about the timeframe in question? Industrial production is doing poorly, a consequence of a medley of issues in “recent” months found in the “latest” numbers. This author will offer no disagreement. Industrial production has been poor for the reasons listed.

But what about the proverbial elephant? Nay, mastodon! The one standing unremarked upon in the room?

The index of industrial production was reported to be 109.7 at the time. That is only 4.1% higher than in December 2007. US industrial production has grown 4.1%. Not per year. But in 12 years. Total!

But no matter how many sofa cushions have been gored by the pachyderm’s tusks, few acknowledge it.

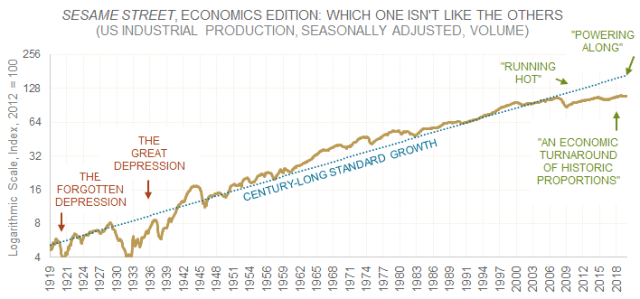

The US Federal Reserve tracks industrial production with monthly data stretching back to January 1919. In the last 100 years, US industrial production fell well-off trend growth and stayed there only three times: from 1920 to 1921, during what James Grant dubbed the Forgotten Depression, and during the Great Depression. The third time? In the present day. Of course, the first two instances were properly fussed about, but today there is only the sound of silence.

The second observation:

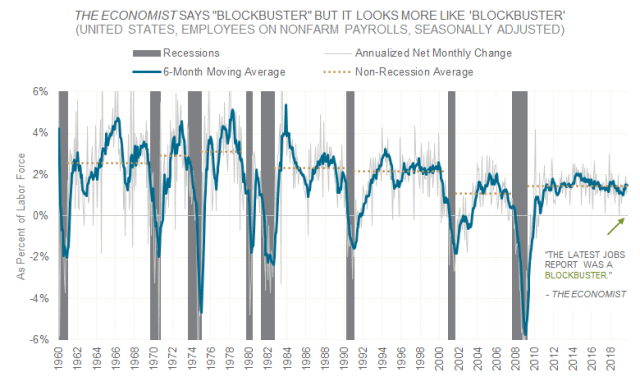

“But, fortunately, such industries only make up a small share of the whole economy. And that is doing rather well. The latest jobs report was a blockbuster, with the economy adding 266,000 positions (well above the expected 180,000).”

The November jobs report was a “blockbuster” because the US economy added 266,000 positions. Is 266,000 good? Well, it is better than the expected 180,000.

When the White House trumpeted these results, it emphasized “smash[ing] expectations.” As per the Council of Economic Advisers, “November’s impressive gain greatly exceeded median market expectations by 44 percent and brought 2019’s average monthly job creation to 180,000.”

The council and financial media agree: November was great because economic forecasters were super wrong.

But the question remains unanswered: Is the 266,000 number, later revised to 261,000, any good? What about 180,000? Are any of these numbers good?

The answer is no. They’re not. None of them.

Not only is 266,000 not good, it is actually bad. In something of a coincidence, the median monthly employment growth during the 1990s outside of recession, adjusted for the size of the labor force, is also equal to 266,000. Put another way, what was average during the 1990s is “blockbuster” today.

If we define “blockbuster” as results in the top 90th percentile, use the 1990s and 2000s as our control group, and adjust for today’s larger US labor force, then we would need between 317,000 and 433,000 jobs a month. And that’s if we’re being conservative. The 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s saw much bigger job gains as a proportion of the labor force.

Finally, for any surviving readers, your author comes to the magazine’s final note:

“GDP growth is trundling along at an annual rate of about 2%, very respectable by international standards. If this strong performance endures, Mr Trump will have a big advantage when he seeks re-election next November.”

Synonyms for “trundle” include: “roll,” “plod,” “shuffle,” “slog,” “trudge,” and “waddle.” Might this be an example of two nations divided by a common language? This American is confident that The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) will not list “gliding,” “sprinting,” “galloping,” or “striding” as synonyms of trundling. This, we are told, is “very respectable by international standards.”

And indeed it is. The United States is performing admirably. When compared to a world mired in a global depression. That is really an epic standard by which to measure against, a real stretch-goal to set for a country that styles itself the leader of the free world. Not too long ago, the late US political commentator Charles Krauthammer described the country as “a single superpower unchecked by any rival and with decisive reach in every corner of the globe . . . a staggering new development in history, not seen since the fall of Rome.”

But now, President Trump may be able to defend his incumbency atop the, “respectable by international standards” hill? From behind impregnable “waddling economy” fortifications?

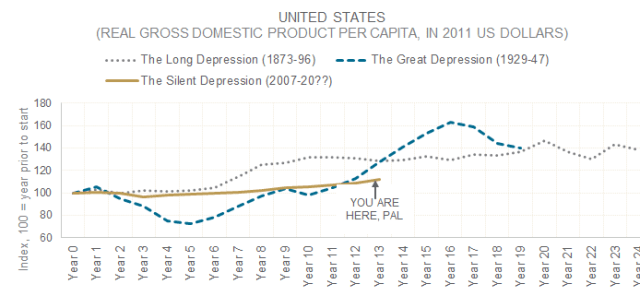

A Silent Economic Depression

Two paragraphs ago, this author claimed that the world was in an economic depression. A depression is not an unrelenting contraction or an uncommonly severe recession. Instead it is the prolonged absence of upside and advancement, a pervasive listlessness where economic opportunity, recovery, and reflation is repeatedly denied, deterred, and deflated.

The financial media’s analysis of the past dozen years, of which the referenced article was but an example, doesn’t see it this way. And has thus inspired your author to crown our current economic doldrums with the sobriquet: The Silent Depression.

This depression is just the third such worldwide economic phenomenon of its kind in the past 150 years. The first was known as The Long (1873–1896) and the second was, of course, The Great (1929–1947). As 2020 represents only its Year 13, the current could not possibly wrest the mantle of “Long” from its predecessor. Moreover, since its initial shock was nowhere near as severe as the 1929–1933 contraction, it doesn’t qualify for the appellation “Great.”

So, why “Silent”? By labeling it thus, your author is referencing the saying, “If a tree falls in the woods and nobody is there to hear it, does it make a sound?” Or, more plainly, if industrial production falls off its century-long trend but the business press is not there to report it, does it count? If monetary technocrats and the political establishment redefine average to mean “blockbuster,” can there be disappointment? If professional economists imply the economy is booming when they say “trundling,” can it be acknowledged?

The Economist‘s blurb sounds positive and impressive. But a closer look at what was qualified, discounted, and left out shows that it’s really saying, “Hey, it could be worse.” All of which is a few hedges short of President Carter’s infamous 1979 speech:

“The symptoms of this crisis of the American spirit are all around us. For the first time in the history of our country a majority of our people believe that the next five years will be worse than the past five years. Two-thirds of our people do not even vote. The productivity of American workers is actually dropping, and the willingness of Americans to save for the future has fallen below that of all other people in the Western world. As you know, there is a growing disrespect for government and for churches and for schools, the news media, and other institutions. This is not a message of happiness or reassurance, but it is the truth and it is a warning.”

When read, Carter’s speech does not come off badly. But that was not how it was received. Many interpreted it to mean that the multi-year economic crisis was due to the average American’s lack of self-esteem. The Carter administration’s gaffe is all the more baffling when the template for a stirring, chin-up, buckle-down speech had been laid out on the silver screen just a year earlier by Bluto:

“What? Over? Did you say ‘over’? Nothing is over until we decide it is! Was it over when the Germans bombed Pearl Harbor? Hell no! It ain’t over now, ’cause when the goin’ gets tough . . . . . . . . , the tough get goin’! Who’s with me? Let’s go! Come on!

“What the [quack] happened to the Delta I used to know? Where’s the spirit? Where’s the guts, huh? This could be the greatest night of our lives, but you’re gonna let it be the worst. ‘Ooh, we’re afraid to go with you, Bluto, we might get in trouble.’ Well, just kiss my [rear sector] from now on! Not me! I’m not gonna take this.”

The US economy has been in suspended animation for 12 years. The lack of upside is so pronounced, pervasive, and oppressive that in Year 13 of the Silent Depression, the growth in real GDP per capita trails what it was during both the Long and Great depressions. The United States is not alone. Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia also trail their performance in either the Great, Long, or both depressions through 13 years. Nor is this an English-speaking phenomenon.

Of the 28 countries with data on real GDP per capita that covers all three depressions, 39% (11) are, as of the end of 2019, forecast to be worse off in Year 13 of the Silent Depression than citizens were at the same point in either the Long or Great Depressions. Only five of the 28 countries (18%) are better off today than they were at similar points during the first two episodes. So, with respect to the recovery in real GDP per capita, of the 28 countries in your author’s study, 82% are forecast to be, as of the end of 2019, in a similar or worse position than they were during the Long Depression and Great Depression.

Economic actors are searching for “bold colors.” Instead of joining that search party, economic pundits labor to cosmeticize “pale pastels.”

A Caveat

There is, of course, an alternative explanation for all of this: Your author does not know what he is talking about.

The Economist has an illustrious staff of Ivy League and Oxbridge graduates. Meanwhile, this author studied at a school not dissimilar to Bluto’s: Arizona State University, winner of the designation “Party School of the Year” for all 13 years of the 1990s.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

Image credit: ©Getty Images/AnkiHoglund

[ad_2]

Image and article originally from blogs.cfainstitute.org. Read the original article here.