[ad_1]

Joachim Klement, CFA, is the author of Geo-Economics: The Interplay between Geopolitics, Economics, and Investments from the CFA Institute Research Foundation.

The war in Ukraine is dominating the headlines. For now.

But the conflict’s indirect reverberations will ripple far beyond the borders of its combatants and their allies. Indeed, they could give rise to new and varied geopolitical risks throughout the world.

The war’s potential effect on the global grain supply and food inflation is especially alarming. Ukraine is known as the “bread basket of Europe,” and together with Russia, it supplies wheat to developing countries across Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia.

There are already reports that many Ukrainian farmers are abandoning their fields right at the beginning of the sowing season to defend their country. The world will pay a price.

The war may lead to a complete or near-complete failure of the 2022 Ukrainian wheat harvest. Russian wheat exports meanwhile may drop to zero as the country diverts its food commodities for domestic use in the face of crippling international sanctions.

Many countries depend on Russian and Ukrainian grain imports to feed their populations. The warring nations are responsible for at least 80% of the grain supply in Benin and Congo in Africa; Egypt, Qatar, and Lebanon in the Middle East; and Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan in Central Asia. All these states will have to find new sources of grain and pay much higher prices for them.

And that will compound an already bad situation. Even before the conflict, food inflation was increasing. Over the last year, it reached 17.6% and 4.8% year over year (YoY) in Egypt and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), respectively. These levels are reminiscent of those that preceded the Arab Spring uprisings back in 2011. The situation is even more extreme in Turkey, where a rapidly declining lira propelled YoY food inflation to 64.5%.

Going forward, several factors may propel food prices even higher. Beyond the lack of grain exports from Ukraine and Russia, spiking energy prices will increase shipping and fertilizer costs. With Russia, a major fertilizer exporter, facing severe sanctions, there will be even more upward pressure on fertilizer prices. This will add fuel to the fire and send food inflation ever higher. In developed countries, while the pain varies across the income spectrum, such trends can largely be ameliorated by reductions in consumer discretionary spending: People adjust by paying more for food and less on travel, entertainment, etc. But in developing nations, where food takes up a larger share of total living expenses and there is less discretionary spending, hunger is a more acute risk.

The Arab Spring is a vivid example of how such conditions can ignite civil unrest and geopolitical tensions. It is not an isolated event. The peasants’ rebellions in the Middle Ages, the French Revolution, and the Revolutions of 1848, for example, all demonstrate how increasing food insecurity can trigger political and social upheaval. The effect is so strong that Rule 6 of my “10 Rules for Forecasting” states:

“A full stomach does not riot.

“Revolutions and uprisings rarely occur among people who are well fed and feel relatively safe. A lack of personal freedom is not enough to spark insurrections, but a lack of food or water or widespread injustice all are.”

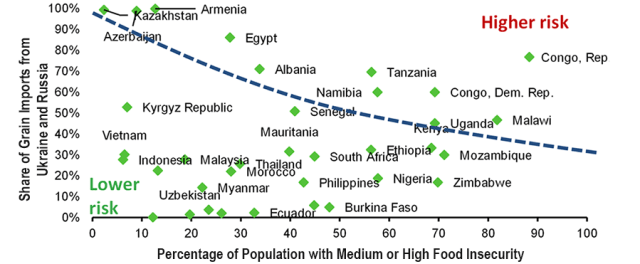

The countries that depend on grain from Russia and Ukraine along with the share of their populations that were at medium or high food risk before the recent conflict are charted in the graphic below. Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan along with Egypt and Congo are among those at the most risk given their reliance on Russian and Ukrainian grain imports, their existing food insecurity, or combination of the two.

Food Insecure and Dependent on Grain Imports from Ukraine and Russia

But high food inflation isn’t the only driver of potential turmoil. Building on recent insights from Chris Redl and Sandile Hlatshwayo, who use machine learning to identify the predictors of social upheaval, we constructed a Civil Strife Risk Index that ranks countries based on five key stability metrics:

- The percentage of their total grain imports from Russia and Ukraine, according to UN Comtrade data

- The share of their populations with moderate or high food insecurity, according to the World Bank

- Their youth unemployment rate based on World Bank and Bloomberg data

- The number of mobile phone subscriptions per 100 people, according to the World Bank

- Their Democracy Index rating from The Economist Intelligence Unit

Why these five components? Evidence suggests that countries with high proportions of young and unemployed men are more prone to instability; mobile phones are essential for organizing mass protest via social media platforms; and a lack of democratic institutions means that the population sees no opportunity to change the political leadership outside of direct action.

Combining these five indicators yields insight into which countries are most at risk of civil unrest. The chart below only includes those that directly import grains from Russia and Ukraine, so it is composed of only those nations that will directly suffer from the fallout of the war in Ukraine.

The Civil Strife Index, by Country

| Rank | Nation | Risk of Civil Strife Index Value | Youth Unemployment Rate | Mobile Phone Subscriptions/ 100 people | Population with Moderate or Severe Food Insecurity | Share of Total Grain Imports from Russia and Ukraine | Democracy Index |

| 1 | Congo, Rep. | 40.5 | 42.7 | 88.3% | 76.7% | 2.8 | |

| 2 | UAE | 32.5 | 9.0 | 185.8 | 53.5% | 2.9 | |

| 3 | Saudi Arabia | 32.0 | 28.2 | 124.1 | 8.1% | 2.1 | |

| 4 | Belarus | 31.3 | 11.2 | 123.9 | 48.6% | 2.4 | |

| 5 | Lebanon | 29.0 | 27.4 | 62.8 | 95.7% | 3.8 | |

| 6 | Nicaragua | 29.0 | 11.7 | 90.2 | 78.1% | 2.7 | |

| 7 | Tajikistan | 29.0 | 17.0 | 5.3% | 1.9 | ||

| 8 | Turkey | 28.5 | 24.5 | 97.4 | 74.8% | 4.4 | |

| 9 | Armenia | 28.4 | 36.6 | 117.7 | 12.7% | 99.8% | 5.5 |

| 10 | Egypt | 28.4 | 23.4 | 93.2 | 27.8% | 86.0% | 2.9 |

The oil exporters — Saudi Arabia and the UAE — and Turkey, with its close trade links to the United Kingdom and the European Union, are the most troubling from an economics and investing perspective. Instability in these countries, could have a spillover effect that disrupts energy supply chains and global trade and triggers renewed spikes in inflation in 2022.

To be sure, Saudi Arabia and the UAE largely avoided Arab Spring-related unrest and should benefit from the rise in oil prices. Nevertheless, their high rankings on the index, driven especially by the youth unemployment rate in Saudi Arabia and the UAE’s reliance on Ukrainian and Russian grain combined with their low Democracy Index scores, may warrant some attention.

The situation in Turkey is particularly worrisome given the country’s already enormous inflation rate and the strong likelihood of a sovereign default in the next 12 months due to the devaluation of the lira.

Investors need to focus on political developments in these countries in the weeks and months ahead. They may serve as an early warning sign of potential global supply chain disruptions that could affect the United Kingdom and Europe.

For more from Joachim Klement, CFA, don’t miss Risk Profiling and Tolerance and 7 Mistakes Every Investor Makes (and How to Avoid Them) and sign up for his regular commentary at Klement on Investing.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

Image credit: ©Getty Images/alzay

Professional Learning for CFA Institute Members

CFA Institute members are empowered to self-determine and self-report professional learning (PL) credits earned, including content on Enterprising Investor. Members can record credits easily using their online PL tracker.

[ad_2]

Image and article originally from blogs.cfainstitute.org. Read the original article here.