[ad_1]

Private real estate funds generally fall into one of three categories. Based on increasing levels of risk and, accordingly, expected returns, a fund’s strategy is designated core, value-added, or opportunistic.

But is this categorization system accurate? Are the realized net-of-fees returns by strategy commensurate with the associated risks?

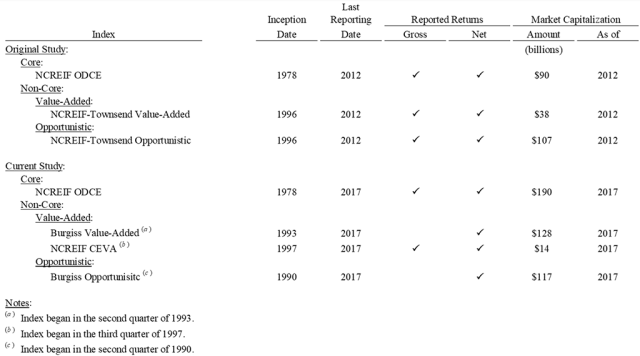

The chart below illustrates the nature of the data sets we employed.

Private Market Real Estate Returns by Category: A Comparison of Data Sources

The risk/return performance of each strategy, before and after fees, from 2000 to 2017, is summarized in the following chart. To improve tractability, we created composite indices from the underlying data sets for the value-added and opportunistic strategies.

Private Market Real Estate Index Performance, 2000–2017

To understand the volatility of value-added and opportunistic returns, it’s important to realize that the standard deviation of net returns understates the potential capital risk to the investor. Why? Because the promoted (or carried) interest paid to the fund manager reduces the upside of the investor’s net return but does not affect the downside risk.

Therefore, the volatility of the gross return better captures the risk of capital loss.

Estimating Alpha from a Levered Risk/Reward Continuum

To assess the risk-adjusted, net-of-fees returns of non-core, or high-risk/high-return funds, we simply applied additional leverage to the returns of core funds.

This levering up creates a risk/return continuum by which we can assess risk-adjusted, net-of-fee performance of non-core funds through the volatility of gross returns. (We estimate the cost of debt to increase with the leverage ratio and, consequently, the risk/return is curvilinear.)

This risk/return continuum is depicted in the following graphic based on the volatility-adjusted performance of non-core funds and the law of one price. To replicate the volatility of the value-added returns, we increased the leverage ratio on core funds to approximately 55%. For the volatility of the opportunistic returns, we boosted the leverage ratio to around 65%.

Estimated Alphas of Non-Core Funds, 2000–2017

Given the identical volatilities, such as those between core with additional leverage and the value-added and opportunistic indices, the “alphas” for indices of value-added and opportunistic fund performance are graphically represented by the vertical distance between the core-with-leverage continuum and the average realized returns of the value-added and opportunistic indices.

The value-added funds produced, on average, a negative alpha of 326 basis points (bps) per year, as demonstrated in the preceding chart, while the opportunistic funds generated a negative alpha of 285 bps.

Estimating the leverage ratio of core funds needed to replicate the net-of-fee returns of value-added and opportunistic funds provides another perspective on the underperformance of non-core funds. As the subsequent graphic shows, investors could have realized identical returns to the composite of value-added funds by leveraging their core funds to less than 35%. (Actual core funds were leveraged less than 25%.)

Estimated Leverage Ratios Required to Replicate Net Returns of Non-Core Strategies, 2000–2017

Had they followed this approach, investors would have experienced less volatility — approximately 650 bps less per year — than had they invested in value-added funds. Moreover, investors could have realized identical returns to the composite of opportunistic funds by leveraging their core funds to less than 50%. That would have meant less volatility — about 700 bps less — than had they invested in opportunistic funds.

Analyzing the Subperiod Performance

The global financial crisis (GFC) devastated the real estate market and non-core properties and funds, in particular. To determine whether the once-in-a-generation event disproportionately tainted these study-long estimates of alpha (–3.26% for value-added and –2.85% for opportunistic funds), we have to analyze performance over different holding periods

The following two charts apply the same methodology to estimate alphas, by strategy, over any subperiod greater than five years. The first displays subperiod alphas for the value-added composite.

Value-Added Funds: Estimated Alpha (with Confidence Level) for Various Holding Periods

What did we find? Every subperiod produced a negative alpha — including the holding periods that concluded before the GFC, when non-core funds would have presumably outperformed core funds.

The last graphic shows the identical analysis for the composite of opportunistic funds. The results are very similar to value-added funds, with substantial underperformance before and after the GFC.

Opportunistic Funds: Estimated Alpha (with Confidence Level) for Various Holding Periods

Clearly, the GFC did not disproportionately taint our study-long estimates of alpha, with measures of –3.26% for value-added and –2.85% for opportunistic funds. Instead, these negative alphas displayed considerable persistence across many time periods.

Why Such Underperformance?

Significant and persistent underperformance by non-core strategies begs the question, Why do so many institutional investors allocate their real estate capital to them?

Our study takes a novel approach to non-core fund performance. Perhaps institutional investors are unaware of these outcomes. Or maybe they’ve dismissed this underperformance as merely a run of bad luck.

Alternatively, institutional investors could (irrationally) create mental accounts for core, value-added, and opportunistic “buckets” — effectively walling them off from one another. Or maybe leverage has something to do with it: Unable or unwilling to apply it, certain investors instead seek higher returns through higher-risk assets.

Another possibility: Maybe public sector pension funds have increased their allocations to non-core investments in response to deteriorating funding ratios.

What Can Be Done?

Whatever the reasons, for investors, this underperformance has a steep price.

All told, the size of the value-added and opportunistic markets and their underperformance adds up to approximately $7.5 billion per year in unnecessary fees. By investing in core funds with more leverage, investors could have avoided them.

So what can be done to minimize the risk of such underperformance going forward?

Investors might consider some combination of the following:

- Allocate more capital to core funds that apply more leverage.

- Demand more and better data on the performance of non-core funds.

- Advocate that non-core investment managers reduce their fees.

- Replace the investor’s fixed preference with an index that has risk/return characteristics similar to the non-core fund.

- Place a fixed ceiling on the fund manager’s incentive fee.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

All posts are the opinion of the author(s). As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

Image credit: ©Getty Images/zhangxiaomin

Professional Learning for CFA Institute Members

CFA Institute members are empowered to self-determine and self-report professional learning (PL) credits earned, including content on Enterprising Investor. Members can record credits easily using their online PL tracker.

[ad_2]

Image and article originally from blogs.cfainstitute.org. Read the original article here.