[ad_1]

Perhaps the biggest tradeoff for equity portfolio managers is between specialization and risk reduction. The fewer stocks they research and include in their portfolios, the better their understanding of the underlying companies and the better their chances of generating excess returns by focusing on their high-conviction positions. On the flip side, the fewer stocks they hold, the greater the likely portfolio volatility and the greater the odds of outsized losses.

So what’s the right balance? As stocks are added to a portfolio, does volatility decrease similarly across all equity portfolio types? Or does it vary depending on style? At what point is peak diversification achieved?

To find out, we compared diversification benefits across eight different portfolio styles: small cap vs. large cap, value vs. growth, dividend vs. non-dividend, and US domestic vs. international.

We built our portfolios out of the top and bottom performance quartiles of the NASDAQ and NYSE stocks corresponding to our various style factors. We constructed a random portfolio from a given number of equally weighted stocks in each style and calculated its volatility using monthly returns over the 15 years from 2005 to 2020.

Then, after selecting another random portfolio of the same size, we conducted the same procedure 100 times, averaging the volatility across all these iterations.

For each style cohort, we came up with an average volatility for each portfolio based on the number of stocks it contained.

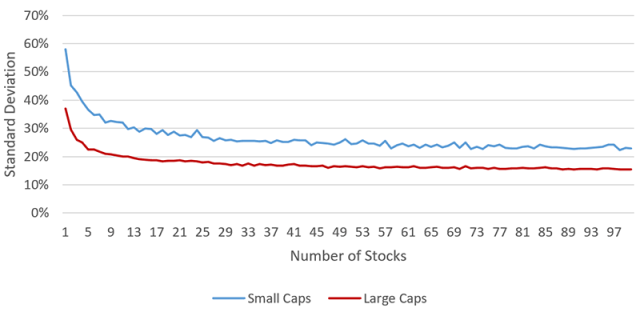

What was the difference between large-cap and small-cap portfolios? The average volatility of a large-cap 10-stock portfolio was 20%. A more diverse large-cap portfolio of 40 stocks only lowered volatility to 17%. So adding 30 stocks reduced volatility by just 3 percentage points.

Peak Diversification: Small-Cap vs. Large-Cap Portfolios

Adding stocks to small-cap portfolios, on the other hand, brought much greater benefits. The average small-cap 10-stock portfolio had a mean volatility of just over 32% compared to 25% for the average small-cap 40-stock portfolio. So 30 more stocks brought more than twice the diversification benefit to the small-cap portfolio than to its large-cap counterpart.

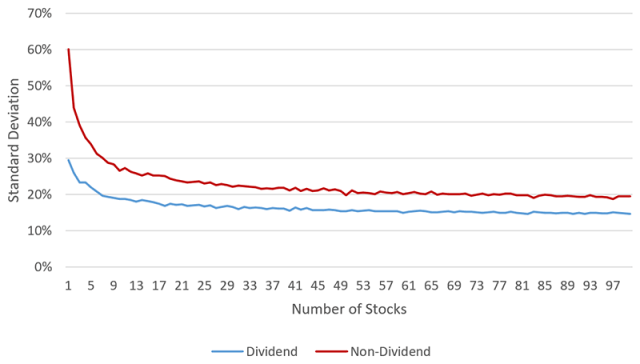

A similar story played out with dividend and non-dividend portfolios. If the average non-dividend portfolio went from 10 to 40 stocks, volatility fell by 5 percentage points on average, from 26% down to 21%. After diversifying the dividend portfolio from 10 to 40 stocks, volatility fell from 19% to 16%.

Peak Diversification: Dividend vs. Non-Dividend Portfolios

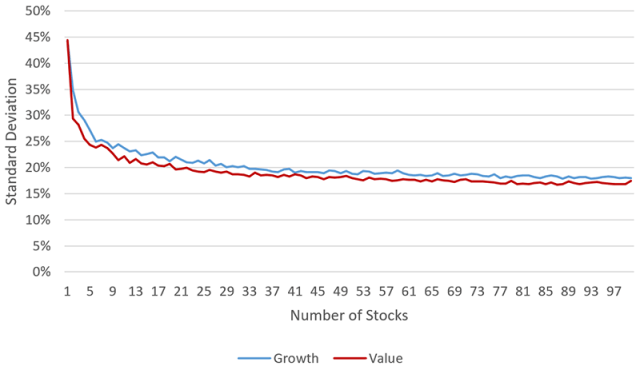

Growth vs. value, however, showed a different relationship: There wasn’t much variation in volatility as the number of stocks increased and the risk reduction was consistent across both cohorts.

Peak Diversification: Value vs. Growth Portfolios

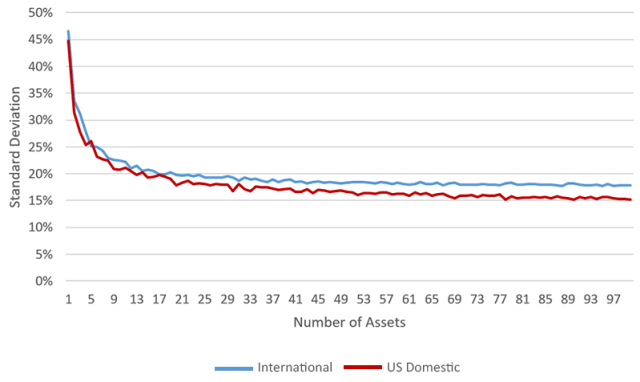

Finally, for portfolios composed of US domestic and international stocks listed on the NASDAQ and NYSE, adding more stocks to the US portfolio slightly reduced volatility relative to increasing the number of stocks in the international portfolio.

Peak Diversification: US Domestic vs. International Portfolio

All in all, these results demonstrate that effective diversification depends on portfolio style. For large-cap portfolios, there’s little to be gained by diversifying beyond 15 stock or so. For small-cap portfolios, peak diversification is achieved with around 26 stocks. The same applies for non-dividend portfolios, while growth and value portfolios need a roughly equal number of stocks to optimally reduce volatility.

So what’s the key takeaway? When it comes to peak diversification in equity portfolios, one size does not fit all. And that’s something equity managers should keep in mind when balancing the benefits and liabilities of specialization vs. risk reduction.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

Image Credit: ©Getty Images / Abstract Aerial Art

Professional Learning for CFA Institute Members

CFA Institute members are empowered to self-determine and self-report professional learning (PL) credits earned, including content on Enterprising Investor. Members can record credits easily using their online PL tracker.

[ad_2]

Image and article originally from blogs.cfainstitute.org. Read the original article here.