[ad_1]

Process Determines Priorities

The baby is crying, and I don’t know why.

Like all babies, my son Joshua cries because he cannot talk. I check to see if he’s wet, hungry, or sleepy. Then I consider less likely explanations: Maybe he’s too hot or too cold, or his clothes are pinching him.

After that, I’m baffled, and it’s easy to entertain crazy ideas: Is there a full moon? Is there a squirrel in his crib? Then I come to my senses and comfort him, hoping that someday I’ll learn what the fuss was about.

Financial news is a lot like a crying baby: First, there is noise and commotion as prices rise and fall. Next, we consider the obvious explanations, followed by the less obvious ones. After that, we’re mystified, so we speculate and hypothesize. The action comes first, and the narrative comes later — if it comes at all.

Narratives Follow Prices

Financial news gives us narratives that are often correct, which is remarkable considering the pressures facing journalists, analysts, and financial researchers. Sometimes the process is comically inept, as I learned early in my career.

In 1985, on my second day of work as a stock analyst, I got a call from the Wall Street Journal. They asked me about the latest move in oil prices, and they quoted me the next day on page two. I was 23 years old, and I was already the voice of authority.

Why did a newspaper call a novice analyst? Oil prices were moving, and they needed an explanation. I can’t remember what I said or if it made sense, but I learned a valuable lesson about news, especially financial news: The narrative follows prices because readers want a story.

In my first five years as a stock analyst at Value Line, I learned to explain price movements in a way that made sense to investors. When we made long-term projections, we diligently followed the fundamentals of each company, the industry context, historical data, and the factors driving the overall stock market.

This was a reliable way to approach stock analysis, and I gradually learned the rules of thumb. When a stock had strong price and earnings momentum, we expected it to continue in the short run. But because we were aware of history, we expected things to return to normal in the long run. Momentum for stocks was like momentum in sports: A player might get hot or cold, but they would eventually go back to their old self.

For growth stocks, we followed current trends, as momentum drove prices up and down. For cyclical stocks, we followed the industry cycle in the short run, and we projected supply and demand in the long run. It wasn’t foolproof, but it worked often enough to keep readers interested and to keep us employed.

History told a story and the story made sense, so the past was prologue for our predictions. Among the analysts, we sometimes joked that we worked for “Extrapolation, Incorporated.”

This was a fruitful approach in the 1980s and 1990s, when long-term trends were firmly in place and the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008 was in the distant future. In those days, a black swan was just a bird, not a freak occurrence that shocked investors and overturned our most cherished assumptions.

My perspective changed when I became a portfolio manager. I ran stock funds in the 1990s at a series of large banks, and I learned that stock prices already reflected expectations and market prices absorbed news faster than I could trade. I also learned that current trends affected current analysis (including short-term estimates and long-term projections), so reading more research did not necessarily help me make better decisions. News is descriptive in nature, not predictive, and this makes all the difference.

Yes, I still had to read consensus estimates to understand investor expectations. And I still had to read the news to help me understand current events. But I was reading more and learning less, and I felt overwhelmed by information.

Tips from Other Portfolio Managers

Fortunately, in 1993 a senior portfolio manager gave me great advice:

“‘Half the research on your desk is a complete waste of time. Figure out which half is garbage and you’ve just doubled your productivity.’

“His point was that most research is backward-looking rather than predictive. Reading obscure financial information may look and feel like productive work, but most of this content has little chance of leading to better results.”

This quote comes from “How to Read Financial News: Tips from Portfolio Managers,” which I wrote in 2016. I interviewed my peers and described how they read the news. In this and the forthcoming articles in this series, I will describe how I apply these lessons as an independent adviser. To put my reading habits in context, I will explain my investment process and my approach to decision making.

Our Process Determines Our Priorities

Setting Our Reading Priorities

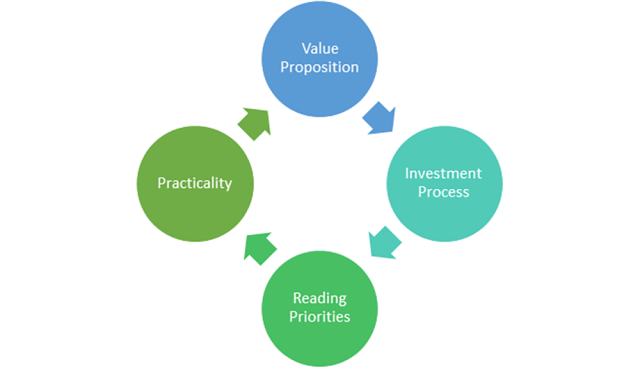

Ideally, the value proposition of our firm determines our investment process, and this drives our reading priorities.

Consider the chart above: Are our reading priorities driven by the investment process and our firm’s value proposition? Or does our reading depend on our personal preferences? Are our reading goals feasible, or are they merely ambitious dreams?

My reading habits reflect my role: I own a registered investment adviser (RIA), and I provide holistic financial advice. The firm is fee-based and independent and builds customized portfolios of diversified funds. I am a solo adviser, and I spend most of my time listening to clients and monitoring the market.

I am especially interested in the assumptions that investors are making about the future. Market prices reflect investor expectations and conventional wisdom, so I want to know: Are consensus expectations reasonable? Optimistic? Pessimistic?

No More Stock Picking

I’ve been a stock analyst for most of my career, but today, I build portfolios using funds. My time is limited, and my top priorities are asset allocation and risk management. I want to get the most out of every hour of research, so these days I’m studying China, as the center of economic gravity shifts to the East.

Studying an individual stock, however, just doesn’t have the same impact on client portfolios. There are only so many hours in a day, and it pays to focus on the core of portfolios and not the satellite.

Practicality

As the chart demonstrates, the investment process determines our reading priorities. We need goals that are feasible, since each of us has limits on our bandwidth. Let me be blunt: I have a baby, a wife on night shifts, and chronic pain from an autoimmune disease. So I don’t pretend to read five newspapers each day before 6:00 a.m.

I can speak candidly because I own the business. Others probably need to be more tactful when discussing work/life balance with colleagues. Nevertheless, an honest self-assessment of our capacity will improve our effectiveness as readers and investors. And it may reduce our stress.

Simple Rules for Decision Making

My asset allocation process focuses on the US economic cycle, and when the leading indicators start flashing red, I raise cash for clients. It’s not rocket science.

You could say that my investment process is just an algorithm — fair enough. But using an algorithm does not mean going on autopilot. As Paul D. Kaplan observed in Frontiers of Modern Asset Allocation, “Historical statistics should not be blindly fed into an optimizer.”

We always have to ask if the algorithm, which is a model of the world, is working the way it was designed to work. After all, models represent the market, and models are not reality. As Alfred Korzybski said, “The map is not the territory.”

If I were to summarize my rules for decision making, I’d point to Daniel Kahneman’s strategies for decision making. Here is how I apply his rules of thumb:

- Trust algorithms, not people: Use simple rules rather than personal discretion. It is a perennial temptation to tweak the process, but this does not add value.

- Take the broad view: Frame the investment process as broadly as possible. As AQR notes, our inputs include historical experience, financial theory, forward-looking indicators, and current market conditions. We don’t look at these inputs in isolation — we take a broad perspective that includes all of them and try to integrate them into a coherent whole. Unfortunately, the market doesn’t talk, and financial news is like a crying baby, so our narrative isn’t always coherent and it’s never really complete.

- Test for regret: Clients who are prone to regret tend to bail out at the bottom of the market, so assess their risk tolerance for any strategy, and put this in the context of the client’s wealth, income, goals, and personality. Client suitability includes far more than mere regulatory compliance.

- Seek advice from people we trust: Our cognitive biases create blind spots, so I stress test my ideas with colleagues. Constructive disagreement is a key ingredient of the investment process, as I observed in “Nine Guidelines for Better Panel Discussions,” which explains how to cultivate respectful disagreement on a discussion panel and has insightful quotes from nine of my peers. We need to cultivate our own network of trusted confidantes. Find people with integrity and learn to harness the power of their insight and criticism. An investment in these relationships is an investment in our careers.

Now that I’ve described my decision making and my process, I will outline my framework for reading financial news.

A Framework for Reading Financial News

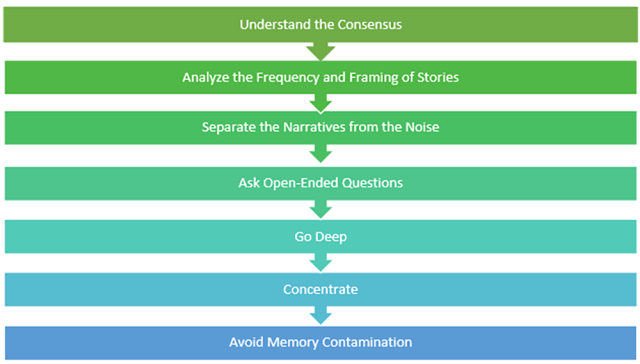

Understanding Consensus

Above, I described how financial news is like a crying baby: There is noise and commotion followed by a narrative that may or may not make sense. Narratives follow prices because readers want an explanation, and a consensus eventually emerges.

This consensus forms a narrative, and the consensus is also embedded in market prices. Since investors look to the future, market prices imply a set of assumptions and probabilities about what will happen. These assumptions may be optimistic or pessimistic, and these assumptions may be coherent or incoherent. Either way, consensus expectations are a logical starting point for putting any financial news in the proper context.

The Usual Suspects

I consult a variety of media, both financial and otherwise, to inform my understanding of the markets and the economy. My daily news sources are the a href=”https://www.nytimes.com/section/todayspaper”>New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and Google News. No surprises there. I also subscribe to The Week, which provides contrasting political viewpoints and catches some stories I might have missed.

For investment news, the four sources below are my favorites when it comes to understanding the consensus. These fall into the “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” category. (They also help me question the narrative — more on that below.)

- Dash of Insight: Jeff Miller provides comprehensive and systematic reviews in Weighing the Week Ahead (WTWA). Miller writes extensively about how to detect nonsense in the financial media and how popularity ≠ accuracy, and he has done excellent work on recession forecasting tools. I have known him for over 10 years, and I trust his judgment and integrity without any reservation. I can say the same about . . .

- Brian Gilmartin, CFA, at Fundamentalis, who gives insightful analysis, particularly about trends in US corporate earnings. He has been at it for a long time, and his experience shows. Like Miller, Gilmartin is independent and publishes consistently, based on a disciplined method, and calls it as he sees it without a hidden agenda. Sources like Gilmartin and Miller are great assets because we can just read their work and get on with our jobs. They’re like finding a lost set of car keys: We can just stop looking, hop in the car, and drive.

- FactSet Insight, Companies and Earnings: John Butters writes chart-intensive weekly reports on aggregate revisions and estimates for the S&P 500. FactSet Insight is simple, authoritative, and free. (FactSet used to offer Dividend Quarterly, among other quarterly reviews.)

- J.P. Morgan 2019 Long-Term Capital Market Assumptions: As an adviser, I make financial plans based on long-horizon expectations about inflation, expected returns, correlations, volatility, etc. The annual guide from J.P. Morgan provides a solid framework, and Guide to the Markets provides comprehensive updates.

Analyze the Frequency and Framing of Stories

What drives the interpretation of financial news? How is consensus formed?

Let’s say there is news about the trade dispute between the United States and China, and I read today’s edition of the New York Times and Wall Street Journal. Here is what I look for:

1. Story Selection

Did each paper cover the story? Was it on the front page? How deep was the coverage? Such editorial choices say a lot about the story.

A single article rarely changes investor sentiment though. I don’t mean that a single event does not change investor expectations, but the coverage of that event in a single article rarely influences public opinion. Story selection, therefore, is not as important as story frequency or story framing.

2. Story Frequency

The frequency of a news story does influence public opinion and investor sentiment. If everyone is writing about a topic, it must be important or at least perceived as such. For example, a slowdown in corporate earnings growth was a popular topic in the fourth quarter of 2018, as was the trade dispute in the first quarter of 2019. The frequency of coverage affects sentiment. So how do we distinguish between fads and trends? I use these three sources:

- WTWA: In his Next Week’s Theme and Final Thoughts sections, Miller teaches investors how to read the news with a critical eye.

- DataTrek monitors trends in Google searches, which helps to quantify the frequency of various stories. Its sample on housing demonstrates the approach.

- The Industrial Sentiment Survey from Corbin Advisors has a helpful wordcloud depicting story frequency trends.

3. Framing

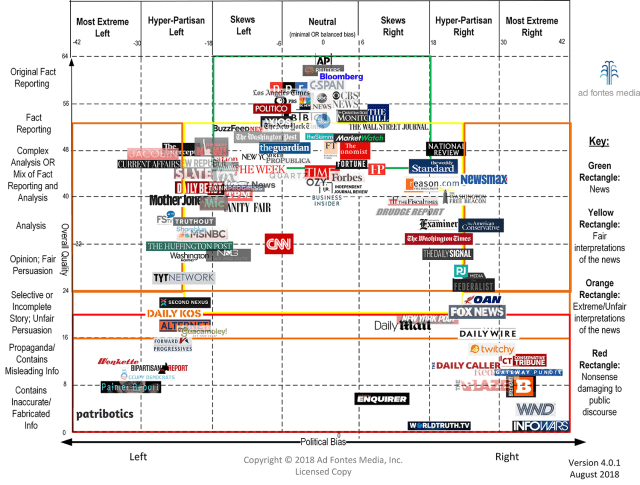

How an event is framed affects the news and how it is perceived. The media can spin a story in countless ways that influence how we interpret it. I read financial news to help understand the world as it is, not how it should be. I identify the political biases of the media and act accordingly, and I do my best to remain nonpartisan. Here are some of the ideological lenses that the media use when covering financial news:

Conservative vs. Liberal: Political bias is everywhere, so we need to spot it quickly, read multiple viewpoints, and come to our own conclusions about the underlying story. We need to keep a particular eye out for changes in how liberal and conservative media cover a story or issue: Editorial deviations from the typical left/right paradigm suggest a significant shift may be underway. When conservative sources frame a story in a liberal manner, or vice versa, something important is happening.

Take income inequality. Left-wing sources, on one hand, have placed it at the center of their economic narrative for years now. The conservative press, on the other hand, may have stories about the minimum wage, student debt, and access to health care, but tends not to frame these around “income inequality” per se. So if Fox News suddenly shifted gears and focused specifically and intently on income inequality, it would be important.

The chart below arranges various media outlets according to where they sit on the liberal–conservative spectrum and how accurate they are as news sources. Created by Vanessa Otero, the chart resembles a normal bell curve, with most sources falling in the middle of the spectrum and a few at the right and left tails of the curve.

Are the media outlets conducting original unbiased reporting? Are they fabricating stories wholesale? Or are they simply putting an ideological spin on news reported elsewhere?

Media Bias Chart

Optimistic vs. Pessimistic: Some news sources are perpetually upbeat about business and the economy. Others are permabears. We need to read both varieties and make our own interpretation.

- In “Jobs Report Has Food for Both Bulls and Bears, a Classic Case of Confirmation Bias,” I demonstrate how we see what we want to see. In the jobs report example, optimists focused on payroll growth, and pessimists on the labor force participation rate. These are two different ways to frame the same data.

- People are systematically pessimistic about global trends, according to Hans Rosling in Factfulness. This phenomenon is widespread across countries and professions. Moreover, 10 simple questions demonstrate that nearly all of us have basic facts wrong, and we are underestimating global progress on disease, poverty, literacy, etc. Everyone is prone to bias and factual errors, regardless of their intelligence or leadership skill. And I believe the media are making us more pessimistic: They want our attention, so they stoke our fears. (My two cents: Factfulness shows that people are biased and negative about many global economic indicators. This pessimism suggests that investors are underestimating the health of the global economy.)

Short Term vs. Long Term: A news story could focus on stock returns for a month, a year, or a decade. Depending on the time frame chosen, the stories could come to contradictory conclusions. When I was an editor at The Street, some contributors were short-term traders while others were long-term investors. The contrast led to illuminating discussions or heated debates, depending on the personalities involved.

Reported Results vs. Investor Expectations: One story might say that a company’s earnings rose 20% last quarter; another that the company missed expectations. Both stories are true, but the implications are quite different.

Pro-Business vs. Anti-Business: Income inequality was originally portrayed as a political problem in the New York Times. Meanwhile, the Wall Street Journal focused on how the minimum wage affected business costs and employment. Same story, two narratives.

Pro-Government vs. Anti-Government: Some sources are skeptical of all government statistics but offer no alternative. Others accept reported figures as gospel truth. For some reason, inflation statistics are a big battleground:

The frequency of stories and the framing of narratives around them have an enormous impact on how we perceive and interpret the news and how we survey the investment landscape. As investors, we must develop a systematic framework — a set of filters — to address this issue. But that would merit a book-length discussion.

Understanding consensus expectations are only the first step in the process of interpreting financial news. The next step is filtering the narrative from the noise.

Separate the Narrative from the Noise

Often the consensus is correct and the market narrative reliably explains price action. But I learned early in my career that old narratives cast a long shadow and may obscure the truth.

OPEC and Oil Prices

When it came to oil prices in the 1970s and 1980s, the consensus narrative focused on the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). OPEC controlled oil prices for a long time, and analysts spent countless hours dissecting its every move. And that worked for a while.

But by the 1990s, OPEC’s influence had faded. Only the media hadn’t caught on. So they continued to interpret oil prices through the OPEC prism. Many investors accepted this interpretation and didn’t look any deeper at the oil and energy markets.

That turned out to be a big mistake. Why? Because while OPEC had been the narrative, it was now just the noise. And the conventional wisdom didn’t recognize the shift until it was too late.

A Cautionary Tale from Metallgesellschaft

In the early 1990s, I was a small-cap energy fund manager and global analyst for large-cap energy at Schroders. I studied energy prices, particularly oil futures, refining margins, differentials in prices among energy products, and the earnings mix of the big oil firms — exposure to oil, gas, refining, and chemicals.

In 1993, Metallgesellschaft (MG) took large positions in futures contracts as a hedge. And it all went terribly wrong. By September, MG had bought 160 million barrels of oil swaps, and by December, it incurred a $1.5 billion loss.

MG’s trading dominated the futures market and this affected oil prices, especially as oil traders got wind of MG’s vulnerability. “As long as its huge position was in the market, MG hung there like a big piñata inviting others to hit it each month,” Ed Krapels wrote in 2001.

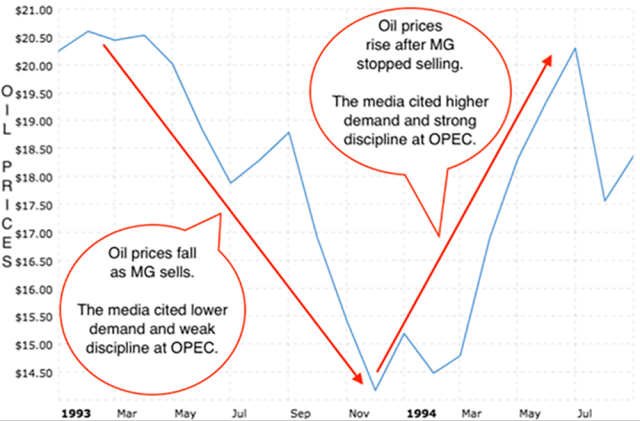

Oil prices fell 30% from April 1993 to December 1993 before rebounding 45% by July 1994. The media blamed the volatility on OPEC and changes in demand.

Oil Price Volatility, West Texas Intermediate, 1993–1994

What Did the Media Say?

Eventually, the media reported on the scandal at MG, and Time included it in its 2012 list of “Top 10 Biggest Trading Losses in History.” But most of the financial literature has focused on MG as a cautionary tale about derivatives and risk management.

Not everyone was fooled. As Krapels observed:

“. . . by Sept. 30, 1993, MG’s positions comprised 16% of all the open interest outstanding in the NYMEX oil contracts . . . According to MG, the position it was rolling over in the market each month was so big that it was distorting the normal equilibrium of supply and demand. The company says its massive position was equivalent to 85 days’ worth of the entire output of Kuwait.”

Unfortunately, very few people picked up on the implications of Krapels’s new narrative. To the best of my knowledge, the rest of the financial media stuck with the traditional explanation: Oil price volatility in 1993 and 1994 could be attributed to the usual suspects — OPEC and supply/demand.

Lost in the Sands of Time

Even after the MG revelations came out, the subsequent news coverage failed to incorporate the new information about oil futures into the narrative. Instead, the media fell back on the old misleading OPEC story.

Financial historians have not done much better. You might think that MG would leave clear footprints in the sand and live on as a moral fable with obvious lessons. But you would be wrong — I had to do lots of detective work to find the right explanation, and I already knew what to look for. Most historians still attribute the oil price volatility of 1993–1994 to OPEC.

Why did I understand these events? Because I was managing an energy fund and had access to sell-side analysts, trading rumors, and the usual assortment of unpublished scuttlebutt — information that most investors and the media can’t access, even after the fact.

So I learned that when you don’t understand why prices are moving, it pays to remember a particular aphorism:

“Maybe someone knows something you don’t.”

This has served me well, especially when the market goes against me. When it’s impossible to separate the narrative from the noise, you might be best served by just liquidating your position.

My Favorite Filters

Some commentators are like noise-canceling headphones. They are original thinkers without hidden agendas and can filter out the static and feedback. I already mentioned Jeff Miller and Brian Gilmartin, CFA, but my two other favorite sources are

Ask Open-Ended Questions

As you study the consensus and the popular market narratives, you will uncover anomalies. This happened to me last year when I read Mary Meeker’s Internet Trends 2018.

Slide 218 showed the global leaders of the internet. A graphic ranked the top 20 public and private firms by market valuation. Curiously, every single company on the list is domiciled in the United States or China.

Why isn’t there a single company from Brazil, Germany, Israel, Japan, or the United Kingdom? There was no clear answer. Intrigued, I dug deeper into tech and China and developed my own theory.

- Economies of scale and network effects create a winner-take-all environment, so market leaders have huge advantages.

- The globe is splitting into two economic spheres: An Asian one where China is preeminent, and another where the United States is most influential.

Inspired by ideas from DataTrek, I delved deeper and found that China and the United States approach technology and privacy and security in vastly different ways.

I am not a tech analyst, but I believe these divergent approaches will affect technological research and development, especially in facial recognition and other aspects of artificial intelligence (AI). Regardless of how this plays out, the results will have profound impacts on investing, economics, and society.

All because I saw slide 218 and asked, Why?

Go Deep

My investment process and reading habits are designed to be streamlined and give me time to go deep. I conduct open-ended research because I believe it has more value than studying daily news and daily price movements. I do not have an informational advantage in trading, so I expect to be the sucker at the table. As an associate told me a long time ago:

“There are investors who are smarter than you, have better tools than you, and who work harder than you. How will you compete with them?”

This doesn’t mean that you never have an edge — sometimes you do. But this advice taught me to be humble about my investment process and to focus on risk management in my positions and portfolios.

I read a variety of white papers, such as Meeker’s, which takes time to digest. This approach isn’t for everyone, but I enjoy it and may even be good at it.

In addition to white papers, I recommend the following:

- The online catalog at your local library: Why search for books on Amazon when your local library will get it for free? My hometown library has online tools to search and request books. Borrowing has two advantages over buying:

- It encourages you to take chances on unknown authors and topics. Maybe you enjoy what you selected or maybe you hate it. But serendipity stimulates your creativity. Personally, I try to read a variety of recent books, just to get a sense of the zeitgeist.

- It imposes a deadline so you don’t wind up with a stack of good intentions. As the deadline looms, you skim the book and learn what you can. And if the book really is good, you renew it.

- Audible: Audio books are great for the car, the treadmill, and other times when you can’t read. I recommend The Great Courses and these two investing-focused lectures:

- Your Deceptive Mind: A Scientific Guide to Critical Thinking Skills, by neurologist Steven Novella, discusses logic, perception, and various cognitive biases. I will cover the fourth lecture, “Flaws and Fabrications of Memory,” in the next installment of this series on memory contamination.

- The Fall and Rise of China, by Richard Baum, studies the historical, cultural, and political roots of modern China.

Concentrate

It takes mental energy to tune out distractions and stay focused, and with a baby in the house, I need every trick in the book. I recommend the following:

- Reduce interruptions: I read long-form material early in the morning or at scheduled times during business hours. I go offline, with no phone, email, or text alerts. Just me and my coffee.

- Use an hourglass: You can’t alway unplug for hours on end, so sometimes I use sand timers to keep from zoning out. There’s something about sand running through an hourglass that helps me stay on task and on schedule.

- Use white noise: For times when you can’t eliminate distracting sounds, you can mask it with white noise, a fan, or an air conditioner.

- Wear earmuffs: I prefer earmuffs over earplugs because they’re easier to put on and take off. I have a huge, ugly pair that lets my wife know I’m “under the dome.” They communicate to people that you’re trying to concentrate. (Just don’t abuse the privilege and tune people out all day.)

- Listen to music: Sometimes I wear earmuffs on top of noise-isolating earphones. It’s a great way to improve the sound of cheap headphones. It can also help you focus, though you will be the last one out of the building if a fire alarm goes off. Instrumental music helps me tune out distractions, and inspirational songs help me plow through paperwork, which I hate with a perfect hatred.

On a side note, I’ve noticed that investment paperwork just keeps getting longer and longer. Now that the forms are stored electronically, there’s no limit to how long they might become.

My prediction? By 2030, the paperwork will be so long, our avatars will read it for us and sign on our behalf.

Prevent Memory Contamination

How often do you say, “I read it somewhere”?

This is what happens when we remember facts but can’t remember where we learned them. This is a form of source amnesia, according to Steven Novella. Source amnesia is normal: We often acquire information but forget when and where we learned it.

Defining Memory Contamination

Our memories form over time as we recall events and create narratives that make sense to us. Our memories are usually reliable, but Novella points out the limitations:

“Our memories are not an accurate recording of the past. They are constructed from imperfect perception filtered through our beliefs and biases, and then over time they morph and merge. Our memories serve more to support our beliefs rather than inform them.”

Memory contamination happens at the time our memories are formed, both initially and subsequently. And if we read both fact and fiction, our memory will have a hard time separating the true claims from the false ones. This is called truth amnesia.

For example, let’s say we hear a rumor that apples cause cancer. We store it in our memory along with everything else we know about apples. And later, when our brains retrieve information about apples, the truth is contaminated by rumors and half truths.

This combination of source amnesia and truth amnesia creates memory contamination. Novella describes this process in Your Deceptive Mind. Memory contamination is not a problem with our ability to recall information. Rather, the flaw lies in how our original memories are formed.

Imagine you spend a day playing softball with friends and follow it up with dinner and conversation. Everyone has an opinion as to why the winning team won the game. Maybe it was the pitching, hitting, or defense. No one can remember every single play, but nevertheless, you create a narrative in your mind.

Meanwhile, as a social creature, you also want to conform your memories to those of other players. So as you discuss the game over your meal, you form a narrative — a memory — that is based on and influenced by those around you as well as their recall of the game, not on the game itself. And that narrative is not actually true.

This does not have to be deliberate deception, but we wind up with a narrative that is misleading, incomplete, or oversimplified.

So what does this have to do with investing?

In my last piece in this series, I described how Metallgesellschaft influenced oil prices in 1993 and 1994. No doubt journalists heard rumors about MG since it was a huge scandal at the time. But these rumors would have been a mix of facts, speculation, and innuendo. The rumors offered no clear and obvious narrative about oil prices. And they clashed with the longstanding understanding that behind every oil price movement lurked the omnipresent hand of OPEC. To counter the OPEC narrative would have meant going out on a limb and contradicting conventional wisdom — and divulging a truth that was not so easily understood.

In these situations, we wind up with a story that is simplistic and with a memory that is misleading.

This is more common than most investors would like to admit. Our memories of financial news and history are probably contaminated with all kinds of inaccurate or incomplete narratives.

And if our memories are contaminated, so are the rules of thumb we use to make investment decisions.

You could say that we suffer from “heuristic contamination.”

Tabloid Journalism

As if this isn’t challenging enough, the media caters to our need for simplicity. We want everything reduced to an easy-to-understand headline, preferably one that confirms what we already know. And the more sensational, the better.

These headlines mix fact with fiction to grab our attention and tend to reduce complex issues to simple cartoons. They are composed in two easy steps:

- Simplify

- Exaggerate

After you create a cartoon version of events, just inject a dose of fear into the mix and voilà! You now have a blockbuster article, ready to go viral.

Let’s say that someone claims that “Corporate earnings are crashing!” This triggers an emotional response that reinforces the memory, regardless of its accuracy.

Repetition also reinforces memories: If lots of sources say that “earnings are crashing,” that will stick with us and we’ll be more likely to believe it is true. This is the foundation of political propaganda: Repeat the dogma until it becomes the truth.

We must be careful with sensational news because this nonsense can plant phony ideas in our heads, like weeds, that eventually creep into our long-term memory.

How to Reduce Memory Contamination

There is no easy way to develop a deep understanding of a topic. In-depth research requires that we consider a variety of perspectives. One way to reduce the risk of memory contamination is to inform ourselves with facts before exposing ourselves to the tabloid version. When we have a fully informed opinion and a broad understanding, sensational headlines have less of an emotional impact.

Here’s how to protect yourself:

- Start with the facts.

- Form your own opinion.

- Check other sources that you know are reliable (in case you missed something).

- Then you can be safely exposed to tabloid news without fear of contamination.

By the way, we can safely skip step four. Personally, I don’t think it’s healthy to read too many sensational headlines. I find that these exaggerations can get mixed into my memory and mess things up.

Even when we are aware of memory contamination, we are still vulnerable to its effects. It’s like dieting: Knowing about temptation does not make you immune from the lure of a hot fudge sundae. So you’re better off if you just steer clear of Häagen-Dazs and Baskin-Robbins.

Likewise, investment knowledge is not enough: You must change your investment process and your reading habits to mitigate your behavioral biases.

Putting It All Together

When I reviewed corporate earnings in early 2019, here are the steps I followed to understand consensus, question the narrative, and avoid memory contamination:

Corporate Earnings in Early 2019

1. Understand Consensus

FactSet Insight, 8 February 2019. This is my source of data about trends in corporate earnings.

2. Form My Own Opinion

Revenue growth in the fourth quarter of 2018 was inflated at 13.3%.

- The energy cycle is boosting aggregate earnings: Revenue growth of 98% in 4Q inflates the aggregate revenue growth for the S&P 500.

- The communications services sector has exaggerated revenue growth: Alphabet/Google was double-counted, and the 2018 numbers include traffic acquisition costs, boosting the sector’s revenue growth from 12% to 20%.

- Looking ahead, revenue growth in 2019 should normalize at 5%, with 5% earnings growth.

3. Question the Narrative

- Fundamentalis, various posts in early 2019.

- Brian Gilmartin, CFA, confirmed the impact of the energy sector on earnings trends.

- He also noted that Apple is dragging down earnings estimates (from 4.9% to 4.2%).

- Dash of Insight, 9 February 2019

- Jeff Miller didn’t raise any red flags about earnings in his weekly review.

- People believe a false narrative that crime is rising in the United States.

Conclusion: My final opinion is unchanged, but I gained some additional depth and insight — without memory contamination.

Why Is It So Hard to Be Simple?

Back in 2015, Jason Voss, CFA, asked, “Which Challenges Do You Face Most Often in Your Professional Life?” The overwhelming majority of poll respondents cited information overload.

There is too much investment data out there, and we feel compelled to consume it all.

Why do we feel the pressure to read so much?

Sometimes we read to show how much we know, to impress clients and co-workers. Sometimes we read because office politics dictate that we keep up appearances. And sometimes we read because we are trapped by our own pride and hubris, believing that we will make better decisions if we read until our eyes turn red.

Relax

Reading financial news does not have to be so stressful. If I had to boil it all down to a few steps, I’d say:

- Understand what clients need.

- Develop a simple investment process.

- Design your reading priorities accordingly.

- Build relationships with people you trust.

- Be accountable for mistakes.

Just do your best, and let the chips fall where they may.

Notes and Further Reading

Prices Follow Narratives

I am not saying that my process is the only way to succeed. I realize that some investors ignore the news, especially if their strategy is based on technical analysis. Moreover, investors who believe in the semi-strong version of the efficient market hypothesis believe that most research is a waste of time, since market prices already reflect publicly available information, both technical and fundamental.

Context: My Process

“Why I Love Having My Own RIA,” Enterprising Investor.

In this piece, I describe the benefits of having my own firm and the importance of autonomy. Independent advisers may lack scale, but owner/operators control the firm from “tip to tail” and can adapt as circumstances change. This makes them more flexible and less hindered by office politics and legacy issues.

Market Wizards: Interviews with Top Traders, Jack D. Schwager.

My investment process fits my personality, and it’s foolish to pretend otherwise. Investors set their investment priorities to fit their overall goals in life, and this happens whether we realize it or not. Commodities trader Ed Seykota puts it this way in Market Wizards:

“Win or lose, everybody gets what they want out of the market. Some people seem to like to lose, so they win by losing money . . .

“I think that if people look deeply enough into their trading patterns, they find that, on balance, including all of their goals, they are really getting what they want, even though they may not understand it or want to admit it.”

“The Peculiar Blindness of Experts,” David Epstein, The Atlantic.

Epstein studies the history of predictions and why they fail. He believes it is better to be a humble generalist who reads widely than a narrow specialist who cares about status and reputation. Epstein’s new book, Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World, expands on these issue.

I agree, and this explains why my interests have broadened. It also explains why I do not publish much anymore: Publishing can make you proud of and defensive of your ideas, which is a trap that leads to stubbornness and poor predictions.

Simple Rules for

Decision Making

My portfolios have exposure to factor tilts, courtesy of Dimensional Funds, but this is beyond the scope of the discussion.

“Historical results should not be blindly fed into an optimizer.” This quote from Frontiers of Modern Asset Allocation by Paul D. Kaplan captures the spirit of the book, which discusses the use and abuse of mean–variance optimization. I wrote a ridiculously long and detailed review of the book for Seeking Alpha.

“Trust Algorithms, Not People”: This quote comes from an extensive interview with Daniel Kahneman that assumes that the investor understands the pros and cons of using algorithms. I wrote about these assumptions in a post about retirement calculators. These rely on a wide range of methodologies that need to be understood and respected. I discuss this in “The Use and Abuse of Retirement Calculators,” which includes an interesting exchange with Kaplan.

“Daniel Kahneman: Four Keys to Better Decision Making,” Paul McCaffrey, Enterprising Investor.

I am a long-time fan of behavioral finance, and Paul summarizes Kahneman’s rules succinctly.

“The Map of Misunderstanding: Interview with Daniel Kahneman,” Daniel Kahneman and Sam Harris, Making Sense.

This podcast covers a wide range of behavioral finance topics, such as the fallibility of our intuitions and the power of properly framing a decision. Harris and Kahneman discuss the replication crisis in science, System One and System Two thinking, the power of framing, moral illusions, anticipated regret, the utility of worrying, and the asymmetry between threats and opportunities.

During minutes 52 and 53, Kahneman gives advice about proper framing, preventing bad decisions, and encouraging good decisions.

At minute 57, Kahneman speaks about the experiencing self vs. the remembering self, and this overlaps with Steven Novella’s work on memory formation.

At minute 60, Kahneman speaks about how good memories come from “finishing strong,” and this suggests that our last impression of an event should be pleasant in order to leave a favorable memory. So plan your vacations to end on a high note.

“Expected Returns on Major Asset Classes,” Antti Ilmanen, AQR.

This article is a brief introduction to Ilmanen’s work. I also recommend:

Expected Returns: An Investor’s Guide to Harvesting Market Rewards, Antti Ilmanen.

Alternatively, you can read a summary of Ilmanen’s work from the CFA Institute Research Foundation.

Analyze the Frequency and Framing of Stories

Story Selection

Journalists typically define “newsworthiness” based on such factors as a story’s impact, timeliness, novelty, controversy, human interest, and proximity to the audience. For details, see “Elements of News Are Immediacy, Prominence, Drama, Oddity & Conflict.”

Some issues are chronically underreported because they happen slowly, lack drama, and cannot be reduced into a simple cartoon. The most underreported stories tend to be good news from distant lands, showing gradual progress by unremarkable people who follow common sense and conventional wisdom. No story there!

As we read financial news, we should pay special attention to stories that are below the radar because they are boring. This type of news is more likely to be underreported and not fully discounted in market prices.

“Media Bias and Influence: Evidence from Newspaper Endorsements,” Chun-Fang Chiang and Brian Knight, The Review of Economic Studies.

Endorsements influence voting when the source is credible, especially when a right-leaning source endorses a liberal candidate, and vice versa, according to Chiang and Knight. So if a media source is credible and endorses a candidate from the “other” party, it is more likely to influence voters.

Vanessa Otero and Media Bias

Why does Otero use a simple left/right political axis? In her methodology, she writes:

“. . . several forces, including our country’s two-party system, tend to flatten those other dimensions into the liberal-conservative dimension that most Americans easily recognize. As Steven Pinker states in his book Blank Slate, ‘while many things in life are arranged along a continuum, decisions must often be binary.’”

For more on this topic, check out:

- Pinker’s Blank Slate

- Max Stearns’s discussion of political dimensionality

- Thomas Sowell’s A Conflict of Visions

Clarification about the Word “Consensus”

In this article, I refer to consensus in two ways: consensus estimates and consensus opinion. A reader pointed out that this was confusing, and I realized that I was using two definitions for the same word:

- A consensus can mean a generally accepted opinion or belief. In the context of news, consensus means the accepted narrative or conventional thinking.

- A consensus also means an “average projected value,” such as a consensus forecast or consensus earnings estimates.

In this article, I discussed the consensus forecast for 2019 corporate earnings. I refer to consensus estimates collected by FactSet, a dataset that averages brokerage estimates of corporate earnings.

Generally speaking, consensus estimates for corporate earnings are considered reliable: It’s hard to come up with a more robust prediction than the wisdom of the crowd. In fact, some people believe that it’s not worth the effort to make independent estimates of corporate earnings since you are unlikely to improve on the accuracy of published estimates.

Do Consensus Estimates Qualify as News?

I am not sure how to categorize earnings estimates and economic estimates. Are these estimates fact, opinion, a measure of sentiment, or something else? Consensus estimates certainly affect stock prices, but they remain an ambiguous category of information.

Separate the Narrative from the Noise: Metallgesellschaft

The estimated losses taken by Metallgesellschaft range from $1.3 billion to $2.2 billion. The losses were caused when oil futures moved from backwardation to contango. Backwardation means that prices are projected to fall with the passage of time, while contango means that prices are projected to rise with the passage of time.

“Re-Examining the Metallgesellschaft Affair and Its Implications for Oil Traders,” Edward N. Krapels, Oil and Gas Journal.

This article offers the best analysis I could find of how MG affected oil prices in 1993. The following excerpts are highlights:

“Press reports [about the MG scandal] began to circulate in early December 1993, and trading of MG’s stock was suspended in Frankfurt on Jan. 6, 1994.”

“The issue of how MGRM’s size affected the oil markets has received much less attention. To our knowledge, there have been only two privately circulated reports dealing with this dimension of the problem, one by this author and one by Philip K. Verleger Jr.”

“As MG’s positions grew, it became by far the largest single trader in the NYMEX contracts. MG’s own analysis came to the conclusions shown in Table 2: that by Sept. 30, 1993, MG’s positions comprised 16% of all the open interest outstanding in the NYMEX oil contracts.”

“According to MG, the position it was rolling over in the market each month was so big that it was distorting the normal equilibrium of supply and demand. The company says its massive position was equivalent to 85 days’ worth of the entire output of Kuwait.”

“NYMEX WTI prices were in contango for much of 1993. Contango may initially have emerged as a result of factors having little to do with MG. But in the course of the next 12 months, it became more and more obvious that other traders were formulating trading strategies that exploited MG’s need to liquidate its expiring long position.”

“Oil Prices Reach 3-Year Lows,” Agis Salpukas, New York Times.

OPEC received the blame for the decline in oil prices:

“The inability of OPEC to agree last week to cut production has sent the oil market into turmoil, with crude oil for January delivery dropping $1.07, to $15.31 a barrel, on the New York Mercantile Exchange. That is the lowest price for domestic crude oil since June 1990, when it traded at $15.06.”

“Oil Price Is Highest in a Year,” Allen R. Myerson, New York Times.

Once again, OPEC’s actions explain the move in oil prices, which are now rising:

“Oil prices bounded today to their highest levels in a year as OPEC oil ministers congratulated each other in Vienna and a report showed that supplies had fallen in the United States.

“Crude oil for July delivery rose 91 cents, to $19.86 a barrel on the New York Mercantile Exchange today, continuing an advance from the $14 range in March.

“Analysts also pointed to fears of a North Korean confrontation with the West over nuclear weapons, and fresh signs that no oil would soon be flowing from Iraq.”

“Crude Oil Falls Below $14 as Heating Oil Prices Drop,” Reuters via the New York Times.

Metallgesellschaft: Prudent Hedger Ruined, or a Wildcatter on NYMEX?Stephen Craig Perrong, Journal of Futures Markets.

Explores the MG scandal in terms of the futures hedging strategy.

“1993 World Oil Market Chronology,” Wikipedia.

Metallgesellschaft is nowhere to be found:

“July: Oil prices plunge on speculation that Iraq will accept U.N. missile test site inspections and receive approval to resume oil exports.

“November: Combination of OPEC overproduction, surging North Sea output, and weak demand lowers the price of Brent to near $15 per barrel.”

“1994 World Oil Market Chronology,” Wikipedia.

Does not mention Metallgesellschaft, not even after the scandal broke.

Ask Open-Ended Questions

Investment Idea Generation Guide, Jason Voss, CFA, CFA Institute.

This book taught me how to read for creativity and rejuvenation. That means leaving my comfort zone and expanding my circles of interest to such topics as geology, demographics, sociology, and history.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

Image credit: ©Getty Images/Barry Winiker

Professional Learning for CFA Institute Members

CFA Institute members are empowered to self-determine and self-report professional learning (PL) credits earned, including content on Enterprising Investor. Members can record credits easily using their online PL tracker.

[ad_2]

Image and article originally from blogs.cfainstitute.org. Read the original article here.