[ad_1]

Most long-time investors are familiar with the herd bias phenomenon, or “the bandwagon effect.” It leads individuals to make investment decisions based on the belief that “everyone’s doing it.”

This type of behavior is part of human nature, though in the context of markets, it’s usually associated with novice retail investors who aren’t confident in their own decision making and thus resort to panic-buying or selling.

For example, recent surges in the price of GameStop shares and the dogecoin cryptocurrency, among others, seem at odds with fundamental analysis and so are commonly attributed to the herd mentality. The same can be said of the dot-com bubble around the turn of the millennium.

When the prices of overbought assets suddenly crash, pundits often view it as confirmation of the prevailing wisdom that the herd is always wrong.

And yet, in the cases of GameStop and dogecoin, Robinhood traders weren’t the only ones driving demand for these assets. Veteran traders and institutional investors were part of the stampede. Many of them made money, and some got burned.

Surely these market participants — with their sophisticated algorithms and years of investing experience — didn’t succumb to a herd mentality. So why did they join the herd?

As the old saying goes, “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble, it is what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

The irony is that most decisions fall in line with the average investor’s decision. That’s just how averages work. If enough people believe their assessment of a situation is superior (when it’s really just average), the herd forms up.

The Illusion of Superiority

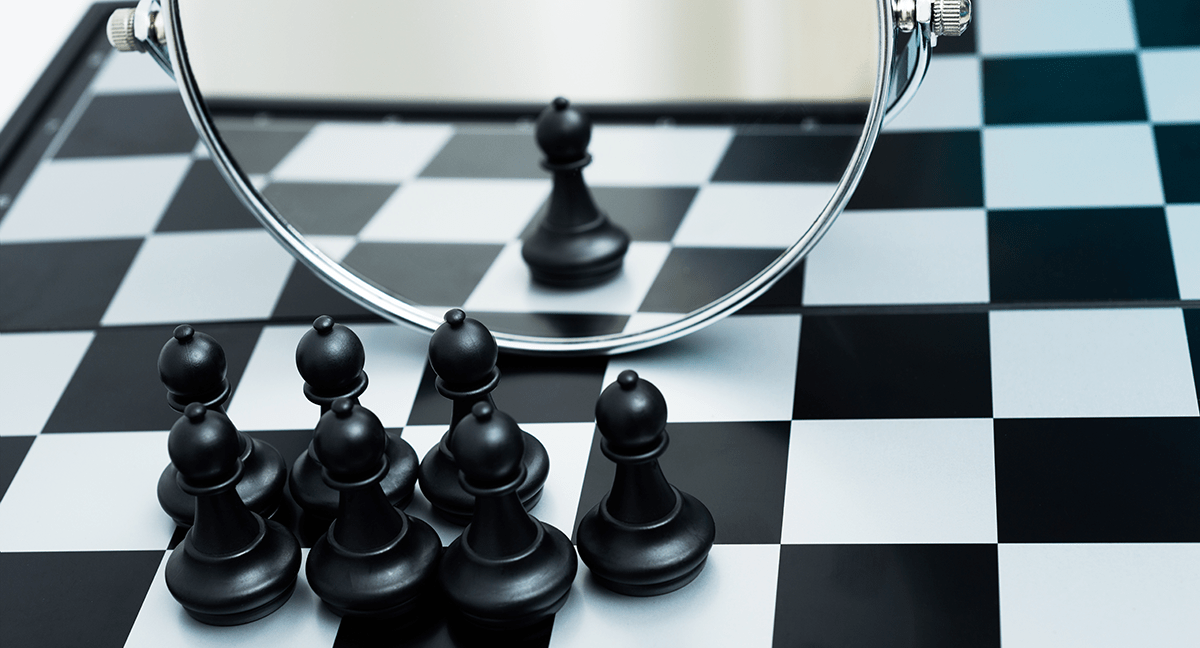

Experienced investors are prone to a different type of bias than the herd mentality — one that can be equally as insidious and is likely more to blame for the GameStop and dogecoin frenzies. It’s called illusory superiority bias, and in short, it’s simply overconfidence that our decision is both superior and unique.

In general, anyone who makes an investment decision that’s backed by a thoughtful thesis believes the decision is correct and ideal. Unfortunately, our impression of what is ideal is often clouded by illusory superiority bias, leading to an incorrect interpretation of facts and an incorrect decision in turn. Sometimes, this investment bias even causes us to consciously or unconsciously ignore facts that don’t mesh with our thesis, again resulting in a decision that is less than ideal.

Illusory superiority bias doesn’t just affect accredited investors of stocks and cryptocurrencies. Venture capital and private equity firms with long track records of success can suddenly find themselves in unprofitable positions due to overconfidence in a particular strategy or method of analysis.

In fact, illusory superiority bias can be found in almost every aspect of life. It’s closely related to what’s known in academia as the Dunning–Kruger effect, a cognitive bias that causes us to overestimate our abilities. This bias paints our perception of everything from our driving abilities to our relative popularity within a group. It’s often harmless. But in the context of money management, it can be downright devastating.

Staying on Guard

So how do we check our investment decisions for signs of bias, whether it’s a herd mentality or illusory superiority? How do we make the objectively correct decision when there are countless variables to consider?

The key is to stick to first-principles thinking, basing each decision on findings and data developed internally. The Theranos debacle proves the wisdom in this advice. The so-called blood testing company helmed by Elizabeth Holmes brought in hundreds of millions of dollars between 2013 and 2015 — before the company’s flagship technology even existed.

In the end, investors and prominent government leaders lost more than $600 million. The flurry around Theranos was perpetuated by otherwise-capable investors who followed and propagated a set of basic assumptions that turned out to be wrong.

Here’s how to avoid this outcome: Stay cognizant of our investment thesis when populating our deal funnel, keep our target criteria front of mind when reviewing each opportunity, and strive to detect when the team is following the lead of outside influence.

This isn’t always easy. It means actively rejecting assumptions of what makes an ideal investor and perhaps even ignoring popular investment strategies. Instead, our focus should be on internally specified outcomes.

Ignore the rumors of funds that returned 100 times the invested capital, and block out the benchmarks that don’t match our cohort or fund lifecycle. Set our objectives and key performance indicators to internally define what success looks like, and set out to achieve those results.

We should aim to engineer the forces we can control while observing those we can’t. By staying disciplined about independence and objectivity, we can avoid such impulsive behaviors as panic buying and selling and be more successful in identifying profitable contrarian positions.

Taking this approach, we’ll probably make fewer investment decisions, albeit smarter ones. At the end of the day, we’ll be less likely to join the herd — and that’s a good thing.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

Image credit: ©Getty Images / baona

Professional Learning for CFA Institute Members

CFA Institute members are empowered to self-determine and self-report professional learning (PL) credits earned, including content on Enterprising Investor. Members can record credits easily using their online PL tracker.

[ad_2]

Image and article originally from blogs.cfainstitute.org. Read the original article here.