[ad_1]

“[The fiscal theory of the price level] says that prices and inflation depend not on money alone . . . but on the overall liabilities of the government — money and bonds. In other words, inflation is always and everywhere a monetary and fiscal phenomenon.” — Thomas S. Coleman, Bryan J. Oliver, and Laurence B. Siegel, Puzzles of Inflation, Money, and Debt

“Monetary policy alone can’t cure a sustained inflation. The government will also have to fix the underlying fiscal problem. Short-run deficit reduction, temporary measures or accounting gimmicks won’t work. Neither will a bout of growth-killing high-tax ‘austerity.’ The U.S. has to persuade people that over the long haul of several decades it will return to its tradition of running small primary surpluses that gradually repay debts.” — John H. Cochrane, Senior Fellow, Hoover Institution, Stanford University

Inflation has set yet another 40-year high. After rising for the last year and despite multiple rate hikes by the US Federal Reserve, the latest Consumer Price Index (CPI) figures came in above estimates, at 9.1%. This suggests inflation pressure may not be easing up at all but may in fact be accelerating.

So, what can be done to tame inflation in the months and years ahead? In the first installment of our interview series with John H. Cochrane and Thomas S. Coleman, the two described how the fiscal theory of the price level (FTPL) explains the inflation phenomenon from both a theoretical and historical perspective. Here they consider how the current inflation surge might be tapped down. As Cochrane wrote in his recent piece for the Wall Street Journal, a monetary policy response alone won’t be sufficient.

What follows is an edited and condensed transcript of the second installment of our conversation.

John H. Cochrane: What will it take to get rid of the current inflation?

There’s some momentum to inflation. Even a one-time fiscal shock leads to a protracted period of inflation. So, some of what we are seeing is the delayed effect of the massive stimulus. That will eventually go away on its own, after the value of the debt has been inflated back to what people think the government can repay.

But the US is still running immense primary deficits. Until 2021, people trusted that the US is good for its debts; deficits will be eventually paid back, so people were happy to buy new bonds without inflating them away. But having crossed that line once, one starts to wonder just how much capacity there is for additional deficits.

I worry about the next shock, not just the regular trillion-dollar deficits that we’ve all seemingly gotten used to. We are in a bailout regime where every shock is met by a river of federal money. But can the US really turn on those spigots without heating up inflation again?

So, the grumpy economist says we still have fiscal headwinds. Getting out of inflation is going to take much more fiscal, monetary, and microeconomic coordination than it did in 1980. Monetary policy needs fiscal help, because higher interest rates mean higher interest costs on the debt, and the US needs to pay off bondholders in more valuable dollars. And unless you can generate a decade’s worth of tax revenue or a decade’s worth of standard spending reforms — which has to come from economic growth, not higher marginal tax rates — monetary policy alone can’t do it.

Rhodri Preece, CFA: What’s your assessment of central bank responses to date? Have they done enough to get inflation under control? And do you think inflation expectations are well anchored at this point? How do you see the inflation dynamic playing out the rest of the year?

Cochrane: Short-term forecasting is dangerous. The first piece of advice I always offer: Nobody knows. What I know with great detail from 40 years of studying inflation is exactly how much nobody really knows.

Your approach to investing should not be to find one guru, believe what they say, and invest accordingly. The first approach to investing is to recognize the enormous amount of uncertainty we face and do your risk management right so that you can afford to take the risk.

Inflation has much of the same character as the stock market. It’s unpredictable for a reason. If everybody knew for sure that prices would go up next year, businesses would raise prices now, and people would run out to buy and push prices up. If everybody knew for sure the stock market would go up next year, they’d buy, and it would go up now.

So, in the big picture, inflation is inherently unpredictable. There are some things you can see in the entrails, the details of the momentum of inflation. For example, house price appreciation fed its way into the rental cost measure that the Bureau of Labor Statistics uses.

Central banks are puzzling right now. By historical standards, our central banks are way behind the curve. Even in the 1970s, they reacted to inflation much more than today. They never waited a full year to do anything.

But it’s not obvious that that matters, especially if the fundamental source of inflation is the fiscal blowout. How much can the central banks do about that inflation?

In the shadow of fiscal problems, central bankers face what Thomas Sargent and Neil Wallace called an “unpleasant arithmetic.” Central banks can lower inflation now but only by raising inflation somewhat later. That smooths inflation out but doesn’t eliminate inflation, and can increase the eventual rise in the price level.

But fundamentally, central banks try to drain some oil out of the engine while fiscal policy has floored the gas pedal. So, I think their ability to control inflation is a lot less than we think in the face of ongoing fiscal problems.

Moreover, their one tool is to create a bit of recession and work down the Phillips curve, the historical correlation that higher unemployment comes with lower inflation, to try to push down inflation. You can tell why they’re reluctant to do that, how much pressure they will be under to give up if it does cause a recession, and the conundrum that any recession will spark an inflationary fiscal blowout.

Thomas L. Coleman: If the fiscal theory is right, then a lot of it has to do with government borrowing and debt. And so it’s looking at what’s the projections, what’s the path of future debt.

Olivier Fines, CFA: The term we like is a soft landing.

Preece: The Bank of England has been quite explicit. They’re saying, “Inflation’s going to surpass 10% later this year, and there’s going to be a recession.” There’s a lot of pain that’s coming, but I’m not hearing the same kind of messaging from the Fed.

We’ve had, in the words of a central bank official some years back, the monetary policy accelerator pressed to the floor but with the fiscal policy handbrake on. We’ve had an era of fiscal austerity combined with very loose and accommodative monetary policies. Does that explain why inflation didn’t take off in the UK and in Europe in the last decade?

Cochrane: Actually, I’d disagree with that characterization. The 2010s were a period of immense deficits by previous standards during an expansion. The “austerity” was a short period of high-tax-rate economic strangulation, but it never produced substantial and sustained fiscal surpluses. And I’m not persuaded monetary policy was that loose. Fiscal policy got really lucky in that for a decade investors were willing to hold and roll over debt at absurdly low interest rates. The interest costs on the debt were low, making it all seem sustainable. That’s about to change in a big way.

The sudden striking emergence of inflation is lovely intellectually, however. There’s a whole category of theories that flowered in the late 2010s. Modern monetary theory [MMT] said that deficits don’t matter and debt doesn’t matter. It’ll never cause inflation. We just threw that out the window, I hope.

Fines: MMT would precisely demand that the central bank become the financing arm of the Treasury. That would be something.

Cochrane: There’s a big conceptual shift that needs to happen throughout macroeconomics. We have hit the supply limits. So, if you thought there was “secular stagnation” and that all the economy needed to grow was more demand, if you thought the central problem of all of our economies was the fact that central banks could not lower interest rates below zero and fiscal policy just could never get around to the massive deficits that would restore inflation-free growth, well, that’s just over. We are now producing at and beyond the supply capacity of the economy. The economic problem now is to control inflation and get to work on the supply side of the economy.

Coleman: Rhodri, back to your question about fiscal restraints. The US actually did not have nearly the fiscal restraint in the 2010 through 2015 period that either the UK or Europe did. But there were efforts and substantive efforts to balance the budget, increase income, decrease spending — and certainly, substantive efforts in that period relative to what we see nowadays. So, I think there were in the US fewer fiscal restraints than in Europe, but certainly more than now.

Cochrane: Europe did go through “austerity” in the early 2010s. In the wake of the European debt crisis, many countries did realize that they had to get debt-to-GDP ratios back under control. In many cases, they did it through sharp and short-run tax increases, which hurt economic growth and were thus counterproductive. Countries that reformed spending did a lot better (Alberto Alesina, Carlo Favero, and Francesco Giavazzi’s Austerity is very good on this). But the effort at least showed a bit more concern with debt than we see in the US. Europe in particular is in better long-run shape than the US in that European countries have largely funded their entitlements, charging middle-class taxes to pay for middle-class benefits. The US is heading towards an entitlement cliff.

The price level looks at debt relative to the long future trajectory of deficits.

Remember that tax revenue is not the same as tax rates. Raising already high marginal tax rates just slows down the economy and eventually produces little revenue. Moreover, it’s especially damaging to the long run, and it’s the long run where we need to repay debts. If you raise tax rates, you get revenue in the first year, but then it gradually dissipates as growth slows down.

So, Europe still has a big fiscal problem, because growth has really slowed down. Growth can even go backwards, as it seems to be doing in Italy. Austerity, in the form of high marginal tax rates, that reduces growth, in fact, is bad for long-run government revenues. At best, you’re climbing up a sand dune. At worst, you’re actually sliding down the side.

Earlier, you said the central banks in the 2010s were doing everything they could to stoke inflation. But it’s very interesting that in our political systems, central banks are legally forbidden to do the one thing that most reliably stokes inflation, which is to drop money from helicopters — to write checks to voters. Fiscal authorities just did that and quickly produced inflation!

There’s a reason that central banks are not allowed to write checks to voters: because we live in democracies. The last thing we want is non-elected central bankers doing that. Central bankers always have to take in something for anything they give. So, this sort of wealth effect of extra government debt is the one thing they’re not allowed to do.

Fines: We tend to think of policy coordination as a negative, the end of central bank independence. When you mentioned coordination, you actually mentioned countercyclical effects between fiscal and monetary policy. Could you say a few words about that?

Coleman: Within the fiscal theory of the price of level, coordination just means that monetary authorities and fiscal authorities work together in one way or another. They may be working in the same direction, or they may be working opposite, but in theory and in the real world there always is some sort of coordination. So, Olivier, you and, I think, people in the markets are using coordination as a negative term, as the monetary authority validating or monetizing debt in support of the fiscal authority. And it’s really important to recognize that when John and I use it, we’re very neutral and that the coordination may be of that form, with the monetary authorities validating and monetizing the fiscal behavior, or maybe what John was just talking about, which is coordinating to reduce the deficit, increase future surpluses, etc.

Cochrane: Yes, coordination is good and necessary. For example, suppose that the central government wants to run a deficit and doesn’t want to borrow money, so it wants the central bank to print money to finance the deficit. It’s happy with the inflation. That needs coordination. That Treasury needs to say, “We’re spending money like a drunken sailor,” and the central bank needs to say, “And we will print it for you, sir. We’re dancing together.”

In the other direction, if you want to get rid of inflation coming from big deficits, and the central bank is printing money to finance those deficits, it’s not enough for the central bank to just say, “We’re not going to print money anymore.” How is the government going to finance its spending? It has to cut spending, raise tax revenue, or borrow. You need that coordination to stop the inflation. And it’s not always easy. Often the government got here in the first place because it didn’t want to, or couldn’t, do any of these.

Central bank independence is quite useful. It’s a pre-commitment of a government that wants to coordinate its actions on a policy that does not inflate, a policy that successfully borrows or taxes to finance its spending. A central bank that tries hard to refuse to spend money is a good kick in the pants to run a sound fiscal policy. So, independence is a way of achieving productive coordination.

Fines: You seem to assume that central bank and government would have a joint interest in keeping inflation at reasonable levels.

Cochrane: Well, yes, and they do. But that’s a long-run desire, and both government and central banks are sometimes tempted. Dear Lord, give us low inflation, but not quite yet — after the election, or once the recession is over.

Also, don’t assume that central bankers always hate inflation and Treasuries always want it. A lot of our central bankers have been for inflation.

But ideally, central bankers are not supposed to want inflation, and their mandates tell them first and foremost to keep a lid on inflation. Our governments created central banks as a pre-commitment mechanism. Governments want low inflation, but they understand that there’s a strong political temptation to goose inflation ahead of elections.

So, an independent central bank with an anti-inflation bias is a way for a government to pre-commit itself to a good long-term policy. It’s like Odysseus who tied himself to the mast so he couldn’t follow the sirens’ song. It’s part of the many institutions of good government that pre-commit to good long-run policies, commitments to respect property rights, to pay back debts (so they can borrow in the first place), to respect a constitution, and so on.

Stay tuned for the next installment of our interview with John H. Cochrane and Thomas S. Coleman. In the meantime, check out Puzzles of Inflation, Money, and Debt and “Inflation: Past, Present, and Future,” among other research from JohnHCochrane.com.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

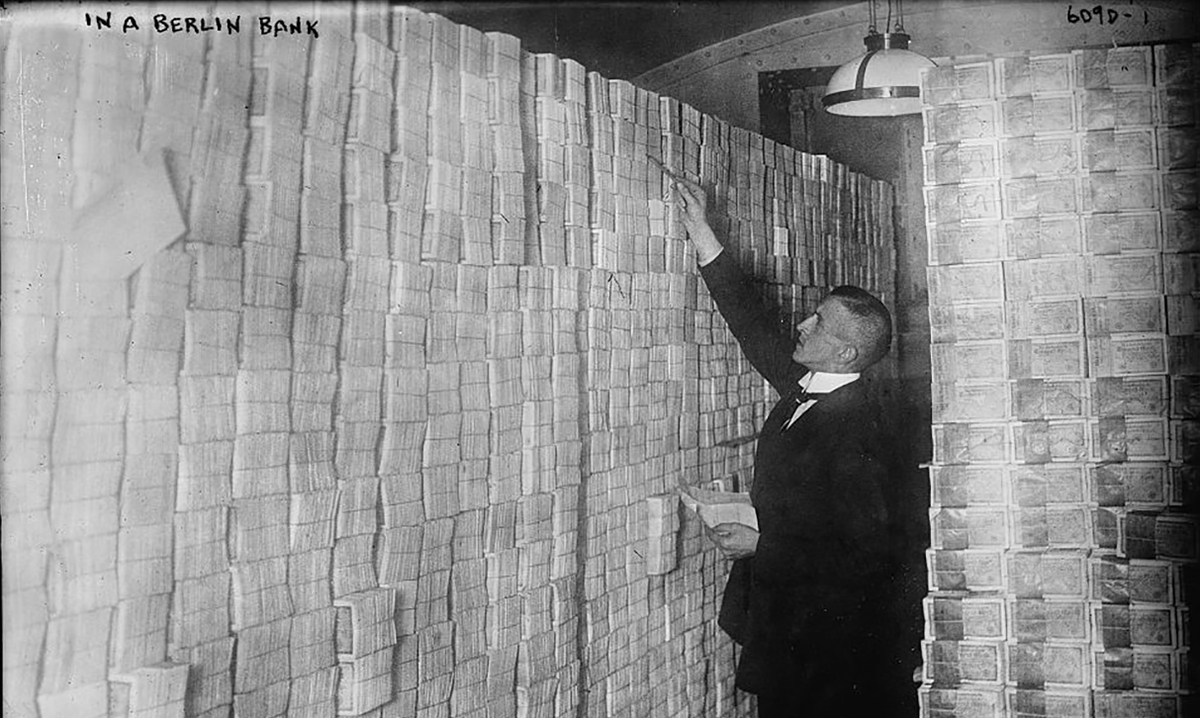

Image courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, [reproduction number, e.g., LC-B2-1234]

Professional Learning for CFA Institute Members

CFA Institute members are empowered to self-determine and self-report professional learning (PL) credits earned, including content on Enterprising Investor. Members can record credits easily using their online PL tracker.

[ad_2]

Image and article originally from blogs.cfainstitute.org. Read the original article here.