[ad_1]

Defining DEI

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives can feel like a “check-the-box” exercise at many companies. But at PNC we’ve made DEI a priority in our investment management services.

Clients now have a fundamental expectation that investment managers can and will apply a DEI lens. Endowments and foundations want data on the racial, ethnic, and gender diversity of the fund managers in their portfolios, and individuals and families want to know how their investments across asset classes are contributing to DEI. And as investment managers, we have to deliver.

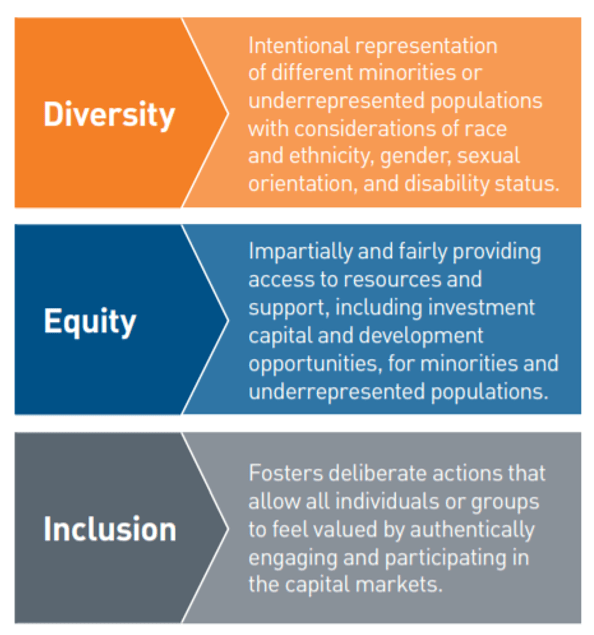

So how did we integrate DEI factors into our practices? First, we developed a working definition to guide us. We describe diversity as the presence of differences that make each person unique. We have evolved this understanding to account for inclusion as the full engagement and development of all employees.

From a corporate perspective, this approach makes intuitive sense. We have more than 50,000 employees with rich and varied backgrounds and we can use these descriptions as the foundation to create a more explicit definition of the types of diversity we assess as part of the investment process.

In our RI practice, we define DEI as follows:

Combined these three elements center the focus of our DEI lens: to intentionally seek investment opportunities in minority or underrepresented populations in an equitable manner that results in:

- Greater representation of minority-owned investment firms.

- Increased assets under management (AUM) for minority-run investment funds.

- Allocating capital toward investment strategies that intentionally consider and engage with companies on DEI criteria.

This working definition gives us the space to develop an investment thesis around constructing portfolios and identify what types of data we need to craft holistic investment solutions.

DEI and Responsible Investing

Inspired by the Impact Management Project, we view RI as a goals-based strategy that takes three principal forms:

- Avoid Harm: We exclude or restrict areas based on certain values.

- Benefit Stakeholders: We assess and engage on environmental, social, and governance (ESG)-related factors.

- Contribute to Solutions: We define a specific, targeted impact and allocate capital toward that objective.

There are many ways to incorporate RI into investment portfolios across asset classes. Over the last decade, traditional financial analysis has increasingly integrated ESG factors. That process involves assessing how companies are managing risks related to racial discrimination lawsuits, for example, or capitalizing on opportunities, say, to reduce carbon emissions. Companies are responding to investor assessments of ESG criteria in novel ways.

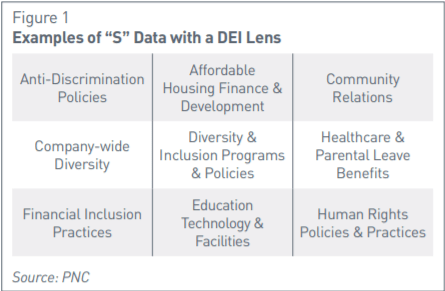

We see assessing fund managers and companies on DEI criteria as falling squarely in the “S” category of ESG, with the intent to “benefit stakeholders.”

The Long and Winding Road

The global COVID-19 health crisis and the demonstrations for racial justice following the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor raised investor expectations that companies would deliver on their DEI commitments. But despite the increased rhetoric around DEI initiatives, some investors remain skeptical of their execution and impact. Companies have taken affirmative stances on DEI before, yet evidence indicates progress has been slow and incremental.

As an example, the Alliance for Board Diversity and Deloitte analyzed corporate board demographics for Fortune 500 companies between 2010 and 2018. In 2018, women and minorities represented only 34% of corporate board seats. That was a 10% increase from 2016 and corporate board diversity demographics are on an upward trend, yet at the current rate of progress, representation will continue to fall short, according to the researchers.

But diversity on corporate boards is just one measure of a firm’s DEI characteristics. Indeed, investors and company management are moving beyond the board room to examine and report on ESG “S” factors that can give insight into how firms treat their employees, engage with the communities in which they operate, and contribute to minorities and underrepresented communities.

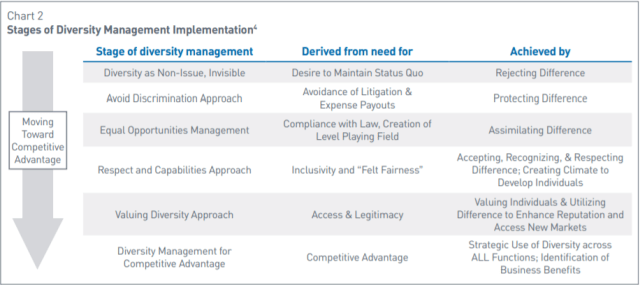

Investors are going beyond compliance with the law and moving further toward integrating and assessing DEI initiatives as a corporate value. Research that compares different companies’ DEI initiatives provides a useful framework for evaluating how these firms are progressing in their diversity efforts. There are six stages of diversity management implementation from “no consideration” to “risk mitigation” to DEI for “competitive advantage.”

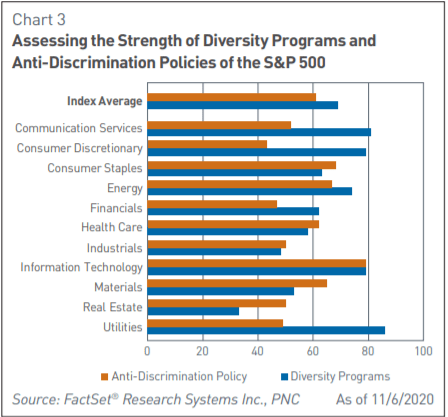

In the S&P 500 Index, for example, DEI characteristics often vary by sector. In November 2020, we assessed the S&P 500 constituents’ diversity programs and anti-discrimination policies and found that, on a 0-to-100 scale, with zero indicating no programs or policies and 100 very strong ones, the S&P 500 averages a 69 score on diversity programs and 61 on anti-discrimination policies. These figures suggest that most S&P 500 companies are going above and beyond legal compliance on these issues.

Of course, 99% of S&P 500 companies have market capitalizations of more than $10 billion. So they likely have the resources to dedicate to and report on DEI efforts, and given the relative strength of these initiatives, these firms seem to view DEI as a competitive advantage and are managing material human capital risks more effectively.

And yet, when we compare results across the 11 sectors that compose the index, there are key differences. For instance, Utilities companies score 86 on their diversity programs but only 49 on discrimination policies. The data also suggests the Real Estate sector has considerable room for improvement. Its diversity programs come in at just 33 and anti-discrimination policies at only 50. Information Technology (IT), on the other hand, does well across the board, with marks near 80 for both indicators.

Given the competitive pressure to attract and retain top talent, S&P 500 firms generally have a greater need for strong diversity programs. This could contribute to the high scores among the IT, Communication Services, and Consumer Discretionary sectors. When we look at material ESG risks by sector, firms in industries with material human capital risk and weak policies tend to have higher ESG risk scores.

While all companies are exposed to human capital risks by virtue of having employees, the materiality of those risks varies by sector. Utilities and Industrials face other, more significant material ESG risks, including carbon emissions and occupational health and safety, so may not go much beyond compliance on DEI.

Rubber, Meet Road: From Concept to Practice

Investors will continue to ask questions around “S” factors, so by building on our working definitions, we can implement a variety of strategies to construct portfolios with a DEI lens:

- Investment Firms: A DEI lens applied across an entire asset management firm can identify which ones have significant ownership by minorities or underrepresented populations and that have diverse representation throughout the company.

- Portfolio Management: A DEI lens can help hire diverse portfolio managers, for example, minority-run mid-cap growth funds, and allocate capital to more diverse managers.

- Security-Level Analysis: A DEI lens give insights into the investment thesis of a fund, specifically those funds that consider the DEI policies and practices of the companies in which they invest. This might include anti-discrimination policies, diversity programs, or demographically disaggregated data on pay equity, employee satisfaction, turnover, and so on. It can also look at diverse company leadership and the products and services of the securities in which they invest.

The lack of DEI data available to investors across these dimensions is a real barrier to implementing a DEI lens to portfolios. Despite our large scale, we have found investment managers are sometimes reticent about sharing gender, race, and ethnicity data.

Diverse Representation as a Metric

Representation is a key indicator in positive outcomes for diverse employees. In this context, representation means diversity throughout the company. (We’ve adapted our definition of representation from “Four for Women” from the Wharton Social Impact Initiative and MLT Black Equity Workplace Certification framework). Demographic data is key to assessing representation, and in the manager selection process, diversity should be demonstrated throughout an organization, not just in entry-level positions or in siloed functions.

Representation is a critical consideration for firms and its importance is hard to overstate. Black people compose about 12% of the US workforce, which is in proportion to their share of the general population (13.4%). Yet after decades of corporate diversity initiatives, only 8% of managers and fewer than 4% of CEOs are Black.

Representation also matters for investment firm ownership and management. A 2019 study of asset management firms found that women- and minority-owned (WMO) firms represented only 1.3% of the $69 trillion under professional management. Furthermore, firms with at least 25% WMO account for just 8.6% of all firms in the asset management industry. Even when controlling for firm and fund size, geography, and investment focus, diverse-owned funds performed at least as well as their counterparts, according to the study.

Other DEI Metrics to Consider

Representation isn’t the only DEI proxy. Other dimensions serve as good indicators for such positive outcomes for minorities and underrepresented populations as promotion and retention, access to health care benefits, and pay equity. Collecting this information is important. It is well documented that people of color often face more barriers to career advancement, receive different performance ratings, and otherwise experience adversity at work. In a survey conducted by the think tank Coqual with NORC at the University of Chicago, the majority of Black (58%), 41% of Latinx, and 38% of Asian professionals said they have experienced racial prejudice at work compared to 15% of their white counterparts.

Having managers report on data about these dynamics helps identify quality companies and employers that are likely to create healthy work environments and improve the livelihoods of their minority employees and stakeholders.

Conclusion

Just as different asset classes offer different risk-reward profiles, so too do varied DEI-based goals offer varied implementation strategies. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to implementing a DEI lens to portfolios. But there are important considerations for asset managers. They can research the diversity make-up of investment firms and fund managers. They can investigate how investment firms and portfolio companies assess their organizational climate for tolerance for discrimination and diversity. And they can analyze how a company’s products and services might support communities of color.

While the arc of moral justice might be long, so too are most investors’ time horizons. Not all social and environmental issues can be addressed through the capital markets, but for investors looking to invest with a DEI lens, their portfolios can bend toward justice, too.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

Image credit: ©Getty Images / John Lund

[ad_2]

Image and article originally from blogs.cfainstitute.org. Read the original article here.