[ad_1]

Time and again throughout my career I have ranted about the nonsense of benchmarking in all its forms. By now I have given up on the hope that business and investing will ever leave the practice behind, so I don’t expect this post to change anything except to make me feel better.

So, indulge me for a minute or come back tomorrow . . .

I spoke recently with a friend about an organization that we are both intimately familiar with and that has changed substantially over the last couple of years. In my view, one mistake the organization made was to hire a strategic consulting firm to benchmark the organization to its peers.

Alas, the outcome of that exercise was the determination that the organization had to be more like its peers to be successful. As a result, the organization engaged in a cost-cutting and streamlining exercise in an effort to increase “efficiency.”

And guess what? Thanks to those measures, many people now think that what made that organization special has been lost and are thinking about no longer being its customer.

The problem with benchmarking a company against its peers is that it tends to be the quickest path to mediocrity. Strategy consultants compare companies with unique cultures and business models to their peers and tell them to adopt the same methods and processes that made their peers successful in the past.

But benchmarking a company that is about to change the world is outright foolishness. In 2001 and 2002, Amazon’s share price dropped 80% or so. If Jeff Bezos had asked the Big Three consultants what he should do, they would have told him to be more like Barnes & Noble.

Name a single company that went from loser to star performer or even changed its industry based on the advice of strategic consultants . . .

Or as Howard Marks, CFA, put it so clearly: “You can’t do the same thing as others do and expect to outperform.”

Which brings me to investing, where pension fund consultants and other companies have introduced benchmarking as a key method to assess the quality of a fund’s performance.

Of course, fund manager performance has to be evaluated somehow. But why does it have to be against a benchmark set by a specific market index?

When they’re benchmarked against a specific index, fund managers stop thinking independently. A portfolio that strays too far from the composition of the reference benchmark creates career risk for the fund manager. If the portfolio underperforms by too much or for too long, the manager gets fired. So over time, fund managers invest in more and more of the same stocks and become less and less active. And that creates herding, particularly in the largest stocks in an index. Why? Because fund managers can no longer afford not to be invested in these stocks.

Ironically, the whole benchmarking trend has turned circular. Benchmarks are now designed to track other benchmarks as closely as possible. In other words, benchmarks are now benchmarked against other benchmarks.

Take for instance the world of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing. Theoretically, ESG investors should be driven not just by financial goals but also by ESG-specific targets. So their portfolios should look materially different from a traditional index like the MSCI World. In fact, in an ideal world, ESG investors would allocate capital differently than traditional investors and thus help steer capital to more sustainable uses.

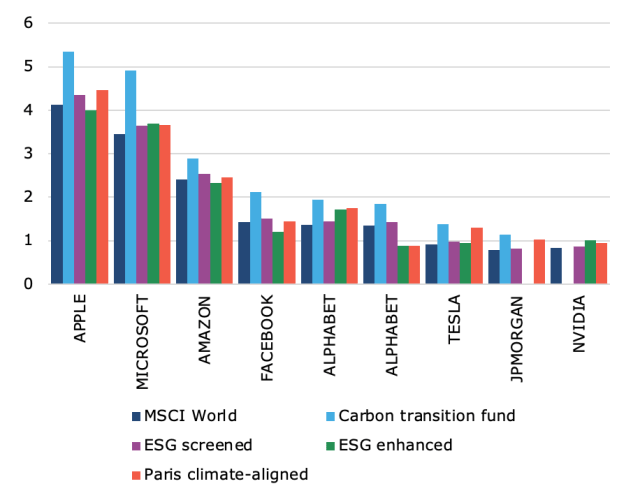

So, I went to the website of a major exchange-traded-fund (ETF) provider and compared the portfolio weights of the companies in its MSCI World ETF with the weights in its different ESG ETFs. The chart below shows that there is essentially no difference between these ETFs, sustainable or not.

Portfolio Weights (%) of the Largest Companies: Sustainable vs. Conventional ETFs

The good thing about this is that investors can easily switch from a conventional benchmark to an ESG benchmark without much concern about losing performance. That helps persuade institutional investors to make the move.

But the downside is that there is little difference between traditional and sustainable investments. If every company qualifies for inclusion in an ESG benchmark and then has roughly the same weight in that benchmark as in a conventional one, then what’s the point of the ESG benchmark? Where is the benefit for the investor? Why should companies change their business practices when they will be included in an ESG benchmark with minimal effort anyway and won’t risk losing any of their investors?

Benchmarking ESG benchmarks against conventional benchmarks is like benchmarking Amazon against other retail companies. It will kill Amazon’s growth and turn it into another Barnes & Noble.

For more from Joachim Klement, CFA, don’t miss 7 Mistakes Every Investor Makes (And How to Avoid Them), and Risk Profiling and Tolerance, and sign up for his Klement on Investing commentary.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

Image credit: ©Getty Images / Mike Watson Images

Professional Learning for CFA Institute Members

CFA Institute members are empowered to self-determine and self-report professional learning (PL) credits earned, including content on Enterprising Investor. Members can record credits easily using their online PL tracker.

[ad_2]

Image and article originally from blogs.cfainstitute.org. Read the original article here.