[ad_1]

Introduction

The global pandemic continues to be a catastrophe for our civilization. Compounding its effect: Few were insured against it. Sure, Hollywood has churned out plenty of movies about contagious disease outbreaks over the years, but that is where the topic seemed to belong — in the realm of entertainment, not in our neighborhoods.

One organization that insured itself against such disasters was the tennis tournament Wimbledon. It paid about $2 million annually for pandemic insurance over 17 years before COVID-19 hit. The organization’s policy will pay out approximately $142 million to cover the cost of cancelling the tennis tournament in 2020. For Wimbledon, the policy was financially worth it. Of course, the pandemic means the price for such protection has spiked so Wimbledon won’t be renewing it in 2021.

Buying protection against disaster in the form of catastrophe bonds, or cat bonds, is a relatively new development. Cat bonds were first issued in the 1990s after Hurricane Andrew and the Northbridge earthquake, which primarily affected the US states of Florida and California, respectively. Prior to these two disasters, in order to issue property insurance, insurers were required by law to cover the damages of such events. But the damages from these two were so severe, that covering them rendered many insurance companies insolvent. So cat bonds were developed in response.

From an investment perspective, since such catastrophes tend not to be caused by the economy and capital markets, creating a diversified portfolio of insurance policies might constitute an attractive investment opportunity.

So how have cat bonds performed over the years?

The Insurance-Linked Securities Industry

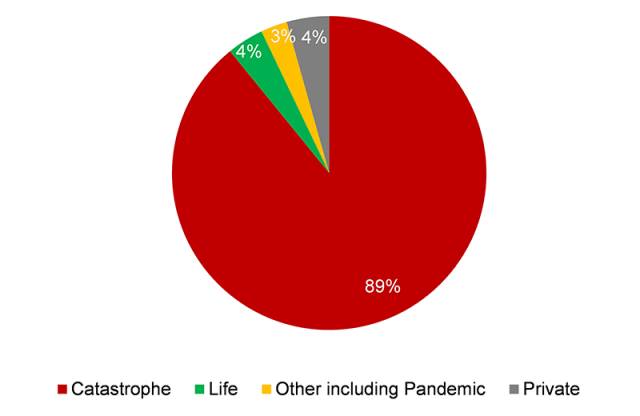

The market for insurance-linked securities (ILS) is tiny. At the end of 2020, it measured $118 billion in outstanding bonds compared to the more than $3 trillion invested in hedge funds and $4 trillion in private equity funds. Although the ILS market also includes insurance policies for life and pandemics, catastrophes constitute more than 90% of the risk.

The mechanics of a catastrophe bond are straightforward: The issuer creates a special purpose vehicle (SPV) for a specific disaster, say a flash flood in South Texas. Investors contribute the principal, which is transferred to a collateral account of the SPV, and receive coupon payments from the issuer until maturity, which is generally around three years. If the defined risk does not occur, then the principal is repaid. If the disaster strikes, then the entire or partial principal will be used to compensate the issuer for damages. Therefore, insurance and reinsurance companies issue cat bonds to transfer risks to other investors.

Insurance-Linked Securities Market: Outstanding Bonds of $118 Billion (2020)

The Composition of Catastrophe Bonds

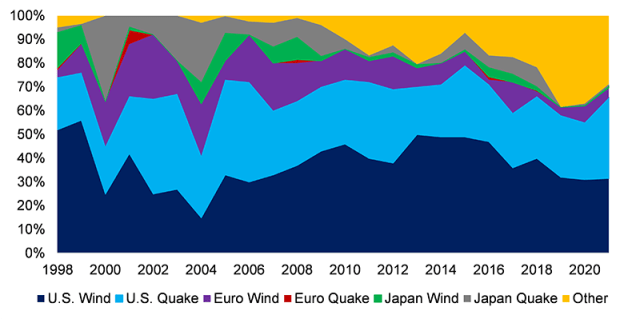

With its fault lines, hurricanes, and flood-prone rivers, the United States is more at risk of natural disasters than Europe. This is reflected in the composition of cat bonds. Approximately 60% of these are focused on US wind and earthquakes. The term wind is used by the insurance industry and may sound rather benign, but it encompasses hurricanes and tornadoes that can devastate entire regions.

Situated between the Pacific and Asian tectonic plates, Japan faces severe earthquake risk, yet surprisingly few cat bonds have been issued there. As capital markets mature and countries grow wealthier across Asia, more cat bonds are likely to be issued as such development tends to bring higher rates of insurance for companies and citizens.

While disaster insurance could no doubt benefit many cities and regions, some risks are just too likely to occur, which makes policies too expensive. For example, many houses on the slope of Mount Vesuvius near Naples, Italy, are deserted since the volcano’s next major eruption, which may occur in our lifetimes, will damage or destroy them.

Composition of Catastrophe Bonds

Rising Losses from Disaster Insurance

One interesting data point: The number of human-made disasters peaked at 250 in 2005 and has fallen to a mere 85 in 2020. The two largest in 2020 were the civil unrest and riots in the United States, which affected 24 states, and the explosion in the harbor of Beirut, Lebanon, which destroyed a significant portion of the city, causing over $4 billion in damages.

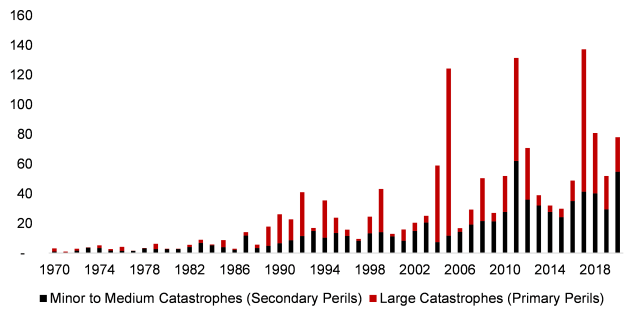

In contrast, the number of natural disasters has spiked from 50 in 1970 to 189 in 2020. This can be ascribed in part to better global catastrophe data, but also to increased urbanization, which creates greater population density, and higher property values. Climate change is another factor that may contribute to this trend.

The damages from catastrophes have been increasing over the last 50 years and have taken off substantially since 2005. The insurance industry differentiates between small and medium-sized catastrophes, or secondary perils, and large catastrophes, or primary perils. The combined damage of large catastrophes in 2005 (hurricanes Katrina, Wilma, and Rita); 2011 (Japan and New Zealand earthquakes and the Thailand tsunami); and 2017 (hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria) amounted to almost half of all the damage from secondary perils since 1970. This pattern obviously raises significant concerns for the insurance industry.

Insured Losses from Catastrophes (US Billions)

Catastrophe Bond Performance

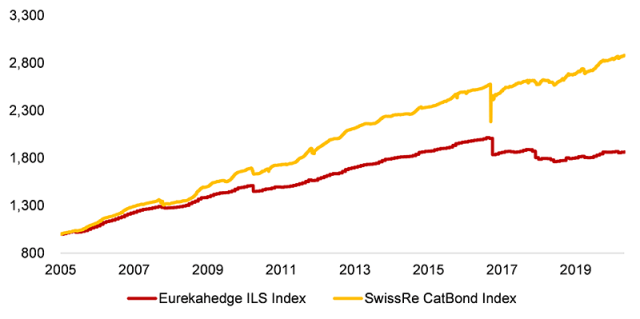

There are two cat bond indices in the public domain with which we can analyze the returns of this unique asset class. The Eurekahedge ILS Advisers Index is comprised of more than 30 equal-weighted fund managers focused primarily on catastrophe bonds. The SwissRe CatBond Index is a diversified portfolio of cat bonds weighted by market capitalization.

The two indices had identical performance trends. The SwissRe CatBond Index achieved a significantly higher return in the 2005 to 2021 period, but that is partially explained by it being gross of fees and transaction costs. Cat bond returns were exceptionally consistent and result in Sharpe ratios of approximately 2. That is significantly higher than those of any other asset class. The largest drawdown occurred in 2017, but the SwissRe index recovered its losses relatively quickly, though its Eurekahedge counterpart did not fare as well.

To be sure, these indices need to be considered carefully: Both overstate their returns. The SwissRe index excludes costs and the Eurekahedge index allows fund managers to import their track records. This incentivizes survivorship bias: Fund managers only tend to import their track records if they reflect well on them.

Performance of Catastrophe Bond Indices

Correlation to Traditional Asset Classes

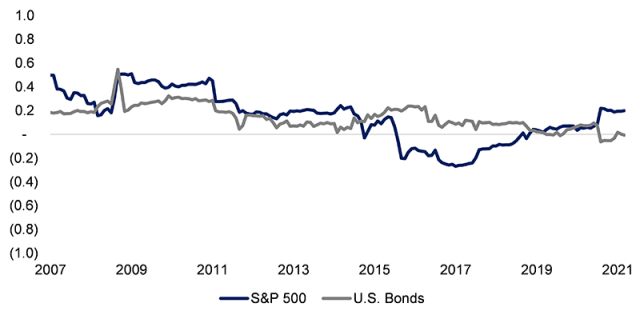

In our view, the Eurekahedge ILS Advisers Index gives a better representation of this asset class’s realized returns since they are net of fees and transaction costs. As such, we will confine the rest of our analysis to that index.

Uncorrelated returns relative to traditional asset classes: That’s the key marketing pitch for investing in cat bonds. By our calculations, the Eurekahedge index’s correlation to the S&P 500 and US bonds from 2005 to 2021 was 0.2 and 0.1, respectively.

Many hedge fund strategies claim to offer uncorrelated returns. But this rarely holds up when stock markets crash. Cat bonds, however, provided attractive diversification benefits during the global financial crisis in 2008 and the COVID-19 crisis in 2020: The correlations to the S&P 500 remained relatively low.

Correlation of Catastrophe Bond Index to S&P 500 and Bonds

Catastrophe Bonds: The Diversification Benefits

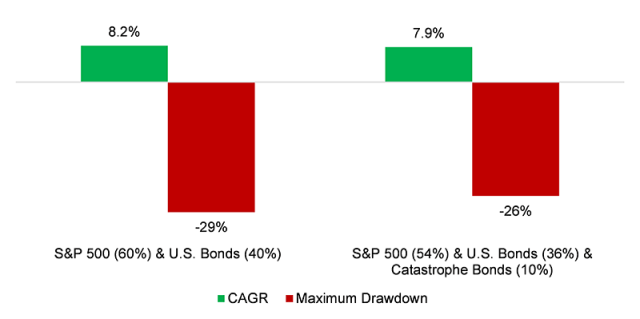

With high risk-adjusted returns and low correlation to stocks and bonds, cat bonds were an excellent diversifying strategy for traditional portfolios. Even though adding a 20% allocation to an equities and bond portfolio would have slightly decreased the annual return by 0.3% from 2005 to 2021, the Sharpe ratio would have risen from 0.90 to 0.95 and the maximum drawdown fallen from 29% to 26%.

Diversification Benefits from Catastrophe Bonds, 2005 to 2021

Further Thoughts

Allocating capital has rarely been as difficult as it is today. Fixed-income, one of the core asset classes, has become structurally unattractive given low to negative yields. But investors who want to reallocate capital from fixed income to alternatives may be delighted by the unique characteristics of cat bonds. Consistent returns, low volatility, few drawdowns, and a low correlation to equities — what’s not to like?

Well, maybe cat bonds have been mispriced historically. Fewer large catastrophes occurred before 2005. But now as more dreadful disasters have been striking more frequently and amid rising property values across the globe, insurance bills are rising. The Eurekahedge ILS Advisers Index has generated a zero return since 2017.

Furthermore, future disasters might affect the global economy to a greater degree, making cat bond returns less uncorrelated. A hurricane in Florida might seriously damage the local economy, but a large earthquake in the San Francisco Bay Area could have a truly global impact.

Investing in cat bonds probably won’t lead to disaster, but it may not be as attractive an insurance policy for portfolios as it has been in the past.

For more insights from Nicolas Rabener and the FactorResearch team, sign up for their email newsletter.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

Image credit: ©Getty Images / Monticello

Professional Learning for CFA Institute Members

CFA Institute members are empowered to self-determine and self-report professional learning (PL) credits earned, including content on Enterprising Investor. Members can record credits easily using their online PL tracker.

[ad_2]

Image and article originally from blogs.cfainstitute.org. Read the original article here.