[ad_1]

In finance, as in all walks of life, people tend to see their environment as predictable. With experience, investment professionals acquire a better understanding of markets, become more confident of their abilities, and conclude that they can interpret the world more precisely.

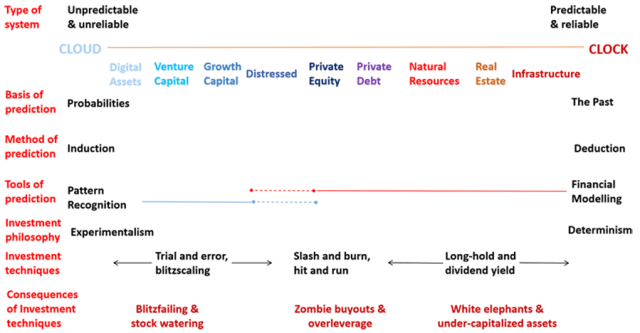

The philosopher of science Karl Popper offered his take on the main issue with such determinism during a 1965 lecture titled “Of Clouds and Clocks: An Approach to the Problem of Rationality and the Freedom of Man.”

He divided the physical world into two distinct categories: clouds, which are “highly irregular, disorderly, and more or less unpredictable,” and clocks, which are their opposites. He observed that it is a mistake to think that everything is a clock. But ever since Isaac Newton, Francis Bacon, and the development of the scientific method, our obsession with logic and order has come to permeate every sphere of human activity.

The Clocks of Leverageable Assets

This mechanical philosophy has been disproved, but much of its ideology remains, hence such oxymoronic phrases as social engineering and political science. Finance suffers from the same self-deception: Investor rationality is a core assumption behind many economic theories.

Alternative fund managers are strong believers in determinism. Even if they hold distinct views of the future, they share a forward-looking approach to deal-making.

They contend that they somehow control the outcome of investment decisions, that the random and the contingent do not dictate returns. Such claims justify charging performance fees that range from 10% to 30%, depending on the asset class and the fund manager.

In that context, infrastructure, real estate, and private equity (PE) firms pursue a deductive investment model. They expect the forecast period to resemble historical performance, give or take a few percentage points of growth. To them, the market is a clock.

Alas, while some scientific experiments are dependable, investments are not. Scientific knowledge is cumulative, deal experience less so. Unlike the rotation of planets around the Sun, the economy is unreliable, rendering financial expertise at times irrelevant. The lack of persistence in performance is now well documented.

Black Swans, White Elephants, and Power Struggles

Infrastructure offers the most regular cash flow profiles of all alternative asset classes. Revenues are more or less clearly defined, sometimes as part of long-term agreements with public authorities.

Infrastructure projects are characterized by exorbitant development costs and monopolistic positions and have high barriers to entry. They can be run like clockwork and suffer lower default rates than other alternative investments, although even real assets can experience prolonged underperformance, as COVID-19-induced government restrictions have shown.

Once infrastructure projects were shut down at the pandemic’s outset, cash flows disappeared practically overnight. Passenger volumes at London’s Heathrow Airport in 2020 and 2021, for example, fell to one-fourth their pre-pandemic levels.

But uncertainty does not have to originate from “Black Swan” events. Because of sheer exuberance, some projects can also turn into “white elephants.” In Spain, the credit-driven construction boom that preceded the global financial crisis led to the building of regional airports that remain underutilized many years after completion.

Other disasters are caused by overconfidence. Financial sponsors and their lenders sometimes employ excessive and unstable quantities of credit, turning their clocks into clouds.

In 2007, KKR, TPG, and Goldman Sachs acquired TXU, one of the largest energy groups in the United States. Prima facie, cash flows derived from a network of pipelines and power plants seem reliable and resilient. Yet within a year, TXU had lost pricing power because of market dislocation. A new source of energy undermined the investment thesis.

Competition from shale gas affected the performance of Texas Competitive Electric Holdings, TXU’s electricity generation division. Demand for its expensive electricity, sourced from coal and nuclear plants, was replaced by demand for cheaper shale gas. Performance tanked, the debt burden became unsustainable, and the company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in April 2014.

The Clouds of Speculative Assets

At the other end of the cloud–clock spectrum are even riskier investment products.

Successful venture capital (VC) investors follow an inductive investment process. They first observe, analyze the situation, and apply their experience to then theorize about the future. Unfortunately, such reasoning relies on inferences made from observations and can therefore lead to broad generalizations, unproven conjectures, and inaccurate expectations and predictions.

Nothing can immediately prove that these inferences are correct. Ultimately, their validity can only be tested through experimentation. Hence the VC preference for failing fast with small amounts of capital at stake. Only inferences that are market tested should be scaled up.

An uncertain future requires an open mindset. The same lockdowns that made physical infrastructure momentarily obsolete unexpectedly boosted demand for video-conferencing and home-delivery start-ups. Nonetheless, the difficulties of forecasting do not detract from its necessity, especially if change is more qualitative than quantitative. Even cloud movements can be anticipated, up to a point.

A constantly changeable ecosystem raises important questions about early-stage investing. The somewhat chaotic nature of the trade means that it is more organic and evolutionary than mechanical. Clusters of start-ups resemble constellations of clouds.

As a result, venture capitalists are voluntarily experimentalists. Entrepreneurial finance uses capital to reshape the economy and create value while dealing with the hypothetical.

By contrast, buyout and infrastructure fund managers can be naively deterministic. They reside firmly in the field of corporate finance, working with discounted future cash flows. They see capital as a tool that can be used to systematically extract value.

Managing Uncertainty

Both real asset fund managers and venture capitalists adopt predictive investment models, but the former’s deductive method is Newtonian while VC’s inductive style is more Darwinian, suggesting a theory of start-up evolution based more on random variations than predictability.

The WeWork saga demonstrates that even at a late stage, a venture’s true potential remains unverifiable. To partly lessen the risk of failure, SoftBank Vision Fund has had to apply hedging techniques by backing multiple participants in emerging sectors. The investment firm funded several rival ride-sharing platforms across the world — Uber in the United States, Ola in India, DiDi in China, and Grab in Southeast Asia. It adopted the same approach with automotive marketplaces, sponsoring Auto1 Group in Europe, Carro in Southeast Asia, Guazi in China, and Cars24 in India.

In casino parlance, this practice is called “voisinage,” the French word for “neighborhood” or “proximity.” At the roulette table, it means betting on a group of adjacent numbers on the rotor of the roulette, which improves the odds of bagging a winner without knowing in advance which number will come out.

Private Capital’s Investment Spectrum

Since executives at the Vision Fund include bankers and corporate executives by training, their knowledge of start-up financing is limited. The extent of their due diligence often consists of shaking hands: SoftBank’s Masayoshi Son famously committed $4.4 billion after meeting WeWork’s founder Adam Neumann for 28 minutes.

Because, in venture projects, track records are often non-existent and projections are more akin to prophecies à la Theranos, spreading bets across a broad range of businesses and segments makes sense.

This is particularly true for alternative assets that mostly have a speculative rather than a productive value. Fine art and digital assets, non-fungible tokens (NFTs) among them, are notoriously difficult to assess. Their valuation is not derived from financial results but from abstruse notions like scarcity and prestige.

Of Clouds and Clocks, Redux

According to the MBTI Institute, only about one in four people have an intuitive personality and are therefore comfortable with abstract concepts. Three quarters of the population have sensing personalities, preferring the tangible world of clocks and market efficiency.

People’s rational expectations and natural inclination towards order make them ill-suited to today’s chaotic environment, which is moving away from physical reality towards virtual platforms, simulated milieus hosted on remote servers in the “cloud.”

Digital disruption has remodeled private markets. The technology sector nowadays represents three-quarters of US VC activity in any given year. It also accounted for almost one in every four leveraged buyouts in 2020.

Technological transformation could completely alter investment risk. While most venture capitalists are fully cognizant of the shortcomings of induction, financial engineers apply a fixed mindset and rarely appreciate the flaws of deduction. There is an abundance of failed start-ups, but zombie buyouts and capital-starved real assets are equally common. This is worth bearing in mind as PE firms increasingly participate in earlier funding stages.

The Newtonian revolution claimed that “All clouds are clocks — even the most cloudy of clouds,” as Popper put it, and led many to believe that the world could be logically explained. However, while analytical judgment is considered universal in science, in finance investment decisions are derived from mental heuristics. These can be enhanced over time, yet overconfidence is their nastiest side effect.

Despite the artificially and falsely deterministic market conditions central bankers have manufactured for well over a decade, now that the everything bubble has started to wobble, investors should keep Popper’s rejoinder in mind:

“To some degree all clocks are clouds . . . only clouds exist, though clouds of very different degrees of cloudiness.”

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

Image credit: ©Getty Images / gremlin

Professional Learning for CFA Institute Members

CFA Institute members are empowered to self-determine and self-report professional learning (PL) credits earned, including content on Enterprising Investor. Members can record credits easily using their online PL tracker.

[ad_2]

Image and article originally from blogs.cfainstitute.org. Read the original article here.