[ad_1]

Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors have become central tenets in the capital allocation process for both the providers of capital, or investors, and the users of capital, or corporations. While initial rounds of ESG investment have largely received undiscerning praise from stockholders and stakeholders alike, most organizations fail to articulate the value proposition of ESG investments and assess if and how such investments have created value.

These shortcomings are perpetuated by the prevailing view that ESG considerations are non-financial in nature, and therefore such a goal can’t be met or shouldn’t even be attempted.

But this view fails to recognize that ESG isn’t non-financial information, but rather pre-financial information.

ESG represents factors that assess the long-term financial resiliency of an enterprise. Given the nature of ESG investments, analysis needs to temporarily set aside typical return metrics, such as EBITDA, profits, and cash flows, and instead concentrate first on how ESG impacts value creation. That is the key to creating the critical connection between investments in ESG and return.

In the short term, an emphasis on value creation would bring much-needed financial discipline to ESG investments and enhance the information value of sustainability reports and disclosures. In the long-term, such a focus can help accelerate the transition of ESG from a market-driven phenomenon toward a standardized principles-based framework.

The Link between ESG and Intangible Value Creation

As the world economy continues to transition to one driven by intangible value, it has clarified the inability of “earnings” to capture value creation via investments. For example, in The End of Accounting and the Path Forward for Investors and Managers, authors Baruch Lev and Feng Gu examine the explanatory power of reported earnings and book value for market value between 1950 and 2013. They find that the R2 declined from approximately 90% to 50% over the period. More recent evidence suggests that the global pandemic has accelerated this trend.

As ESG represents an effort to fill this value creation gap in financial reporting, it is no surprise that as value creation continues to shift to intangibles, so continues the rise and adoption of ESG.

To assess ESG value creation, we must first accept that ESG is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Value creation opportunities for ESG investments are largely a function of the industry in which an enterprise operates. In order to generate economic value from ESG investments, or any investment, an enterprise must generate returns above those required by the tangible assets and financial capital employed. ESG value creation opportunities are higher for companies with a differentiated, value-added, and high-margin business model than for companies with a commoditized, tangible-asset intensive, low-margin business model.

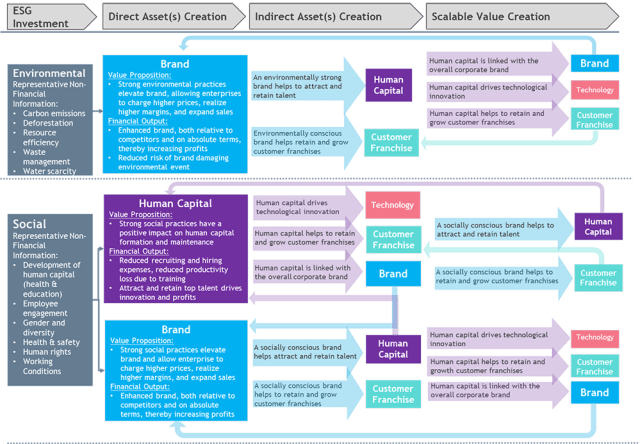

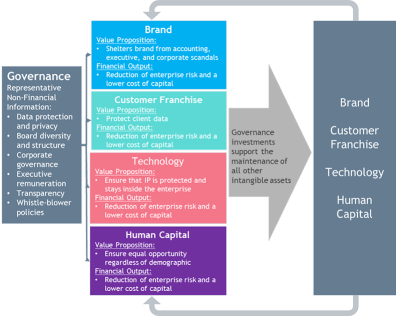

Given the above, it becomes clear that ESG value creation manifests in the formation and maintenance of intangible assets. But which of E, S, and G generate which intangible assets? Answering this question is necessary for enterprises to articulate the value proposition of ESG investments. The following figure begins to provide a framework for answering this question by examining specific groups of intangible assets, including Brands, Human Capital, Customer Franchises, and Technology. It examines the value creation lifecycle through three separate stages:

- Direct Assets: Those intangible assets that are directly impacted by the E, S, or G investment.

- Indirect Assets: Those intangible assets that benefit from the value accretion of the direct intangible asset(s) which was targeted with the E, S, or G investment.

- Scalable Value Creation: The final phase of the lifecycle recognizes that intangible asset value creation via ESG investments is scalable as a result of the interconnection with other intangible assets. Such attributes are why the value created from ESG investments may have little correlation with the investment amount.

Given that intangible asset value drivers are well documented and understood, and now armed with a better understanding of how E, S, and G investments result in intangible value creation, we can identify certain characteristics to assess expected relative value creation of ESG investments between enterprises. Here are six such characteristics, along with brief descriptions:

- Reliance on Brand/Brand Strength: The greater the reliance on brand and reputation for an enterprise, the greater the expected return on ESG investments.

- Reliance on Human Capital: The greater the reliance on human capital for an enterprise, the greater the expected return on ESG investments.

- Value-Added Business Model: The greater the enterprise valuation premium over tangible assets and capital, or the ability to generate enterprise valuation premium, the greater the expected return on ESG investments.

- Nature of Customer Relationships: The greater the connection or exposure to the end customer, the greater the expected return on ESG investments.

- Tangible Asset Intensity: The more a business model relies on tangible assets, the less the potential value to be created by ESG investments.

- Market-Dominant Technology: Propriety technology can create consumer demand that is less elastic to the value of other intangible assets, therefore the more a business model relies on proprietary technology, the less the potential value to be created by ESG investments.

The following chart analyzes these six criteria for five enterprises from different industries. The greater the area covered, the greater the expected value creation of ESG investments.

While the above are certainly six key criteria for ESG value creation, such a framework is not limited to just six criteria, nor does it require the utilization of these specific criteria.

What’s the Path Ahead for ESG?

In the short term, a focus on intangible value creation can bring more financial discipline to ESG investments and bolster sustainability reports to go beyond endless lists of statistics and overtly qualitative narratives.

Longer term, a focus on intangible value creation can facilitate a move toward a financial reporting system that captures intangible value creation. The primary goal in developing a standardized principles-based framework is to ensure the usefulness and relevancy of financial statements. However, the current accounting framework is not only failing to provide relevant information on value creation, but it is also actively constraining efforts to fully implement value-creating ESG priorities.

In a recent article, “Constrained by Accounting: Examining How Current Accounting Practice is Constraining the Net Zero Transition,” the authors analyze BP’s commitment to become carbon neutral by 2050 in the context of ESG and the current accounting model for intangible assets and liabilities. They argue that the current accounting model unduly penalizes and demotivates companies as they attempt to make such investments. This need is no more succinctly articulated than in the authors’ analysis of both technology and brand intangibles, the latter of which is discussed below:

“We postulate that while an organization does not control the environment, its employees, or other stakeholders, it has control of its relationship with those entities, intertwined with its reputation, through the alignment of its decisions with social norms. It follows that the definition of an asset should be applied to an entity’s reputation or its social license to operate, resulting in capitalization and fair valuation of these assets. This treatment balances the requirement to recognize social obligations as liabilities and reduces the punishing treatment of costs related to complying with social norms. Such costs could be viewed as investment in reputation and the potential benefit to the organization from such investment would be capitalized.”

These constraints are not limited to brand and technology, but also exist for human capital. In “Two Sigma Impact: Finding Untapped Value in the Workforce,” the authors note how current accounting drives behavior that limits the value creation opportunities for human capital. The authors state:

“Private equity has tended to view labor as a line-item to be reduced rather than a place to invest, resulting in a large blind spot for the industry. What if there were another, more fruitful way of looking at workforce issues?”

These examples highlight the inextricable link between ESG and the efforts of accounting standard setters exploring opportunities to systematically address intangible value creation. The limitation of accounting frameworks to systematically address intangible assets is not due to their lack of acknowledgement regarding the importance of intangibles, but rather the lack of a viable framework that is practical, objective, and universally applicable.

A focus on value creation will allow the best ideas, concepts, and frameworks that emanate from ESG to inform the ongoing debate on how to better convey value creation through accounting and financial reporting processes. Building on the initiative shown with ESG, investors can help guide the way toward a solution.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

Image credit: ©Getty Images / SimplyCreativePhotography

Professional Learning for CFA Institute Members

CFA Institute members are empowered to self-determine and self-report professional learning (PL) credits earned, including content on Enterprising Investor. Members can record credits easily using their online PL tracker.

[ad_2]

Image and article originally from blogs.cfainstitute.org. Read the original article here.