[ad_1]

“After the automotive bubble, we had bubbles in aviation and radio; then, in the 1960s, the electronics boom; and various others later on. You can always look back and say that the bubble was justified because of one great company that is still prospering, like IBM or Boeing. But did you want to hold the index of that industry? Probably not.” — Laurence B. Siegel

Every 10 years since 2001, a group of leading investors, finance experts, and academics has gathered for a free-flowing discussion of the equity risk premium. Held under the auspices of the CFA Institute Research Foundation and chaired by Laurence B. Siegel, the forum has featured an evolving cast of luminaries, among them, Rob Arnott, Cliff Asness, Mary Ida Compton, William Goetzmann, Roger G. Ibbotson, Martin Leibowitz, and Rajnish Mehra, to name a few.

Rarely are so many of finance’s top thinkers all in one place, and rarer still is their dialogue so compelling and forthright. We didn’t want to keep these conversations to ourselves, so we transcribed the latest talk, held virtually on 21 October 2021, and transformed it into several lightly edited excerpts that explore some of the key themes in finance.

Take, for example, the bubble phenomenon. How do we define a bubble? How do we recognize one? And what should we do when we think we have one?

Below, the forum participants tackle those very questions and offer illuminating insights on both the nature of bubbles as well as a detailed exploration of the momentum factor.

Rob Arnott: Funny anecdote: My eldest son is somewhat of an entrepreneur, and he came to me in late 2019 and said, “Dad, I’ve got a quarter million I want to invest. Where should I invest it?” I answered, “You’re in tech, so don’t invest it in tech. You’ll want to diversify. Your revenues all come from the US, so you want international diversification; invest outside the US. I’d recommend emerging markets value, but more broadly, I’d recommend diversification.”

He then said, “What do you think of Tesla and bitcoin?”

I replied, “They’re very speculative; they’re very frothy. If you want to go for it, go for it, but don’t put any money into those that you can’t afford to lose.”

So, three months later he came to me and said, “Dad, I put the money half in bitcoin and half in Tesla.” At the end of 2020, he sent me his account statement, and it showed +382% for the year. He asked, “Dad, how’d you do,” and I said, “I’m pretty happy with my 12%.”

It’s awfully interesting to see that what we regard as “bubbles” can go much, much further and last much longer than most people realize. My favorite example is the Zimbabwe stock market during the hyperinflation in the first six weeks of the summer of 2008. Suppose you saw this hyperinflation in Zimbabwe and said, “Get me out of here. In fact, I’m going to take a short position. I’m going to short Zimbabwean stocks, and I’ll do it on a safe, small part of my portfolio — 2% of the total.”

The Zimbabwe stock market, in local currency terms, then rose 500-fold in six weeks as the currency tumbled 10-fold. So, in dollar terms, it went up 50-fold, meaning that you just got wiped out. A 2% short position became a 100% short position. Eight weeks later, the currency had fallen another 100-fold and the market basically dropped to zero and stopped trading. So, you would have been right, but you would be bankrupt. These bubbles are very, very interesting. It is very dangerous to bet against them except in modest ways.

Martin Leibowitz: As most of you know, in the short-term factor studies that people have done, one of the factors that keeps cropping up — with the heaviest weights — is momentum. This is very curious: Why should momentum have that kind of emphasis in these types of analysis? If the market is efficient, would you really expect that momentum would be such a powerful force? I think there’s an explanation for it, but it certainly raises eyebrows.

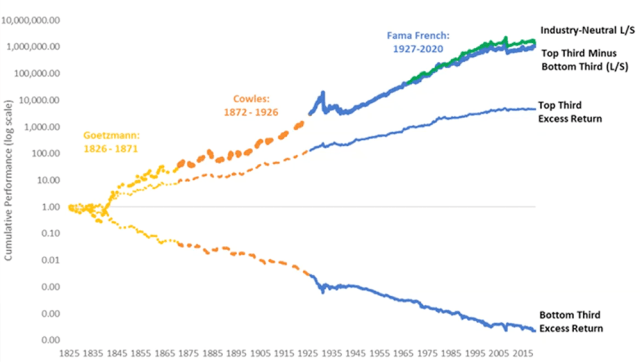

Arnott: We published a paper titled “Can Momentum Investing Be Saved?” This was a deliberately ironic title because how can something that works possibly need saving? Well, it works in the sense that if you buy stocks that have gone up historically, they keep going up. But the effect has a very short half-life, three months or less. The stocks stop going up after about six or eight months, on average, and then they give it all back and then some, which means that you’d better have a sell discipline or you’re in trouble.

That’s why momentum and value aren’t at odds with one another. Value says to buy anti-momentum stocks. Momentum says to buy momentum stocks (obviously). The former is right in the long term, and the latter is right on a very short-term basis. (Cliff Asness is far more expert on momentum trading than I am, so maybe he’ll comment.)

One last observation would be that standard momentum, wherein you build the portfolio using the last 12 months’ return other than the last one month, has not added value since 1999. So, you got 22 years of slight negative returns, overwhelmingly driven by the momentum crash in 2009.

Laurence Siegel: I think Cliff would admit or confirm that momentum can’t really work indefinitely. Cliff, do you care to comment?

Cliff Asness: These are all facts. We knew that before the 2009 reversal, the momentum crash, that it has a bad left tail. Like anything that is asymmetric or option-like, that risk is present. Option replication is essentially a momentum strategy, so there’s something to the analogy between momentum (in stocks) and the return pattern of options.

How many of those left-tail events occur is the variable that drives everything. If you see one 2009-style momentum reversal every 100 years — and, at that magnitude, that’s about what we’ve seen — momentum is fine. Every once in a while it gets killed, but it’s fine. If you see three in the next 10 years, it could wipe out the premium. So, momentum investing is a bet that the next 100 years will look like the last 100.

Monthly Returns on Momentum (top third of stocks by trailing return) vs. Anti-Momentum (bottom third) Strategies, 1826-2020*

Notes: Trailing return: previous 12 months except for previous one month. L/S denotes long-short portfolios of top third minus bottom third, with and without adjustment to make portfolios industry-neutral.

* Momentum are the top third of stocks by trailing return; anti-momentum are the bottom third.

Momentum works a lot better in combination with a value strategy that not only uses value as a metric but also updates the prices fairly frequently, at least at the same frequency as momentum so that they’re highly negatively correlated. I wrote some material on the momentum crash in 2009 in which I showed that if you combined momentum with value, this was actually not a very tough period for our firm [AQR]. It wasn’t a great period, but it wasn’t all that bad because value did so well. So, it’s a classic case of evaluating something in isolation versus in a portfolio. If I were to trade only momentum, I would be somewhat terrified. Not everything we do has a Sharpe ratio that lets us sleep well every night.

But momentum alone? The left tail has been too bad. You can make money for a long, long time like some people are now, and — no one believes it now — they can lose it really, really fast. Momentum is part of a process that’s also looking for cheap and, in a different vein, high-quality stocks. We think the long-term evidence is still very strong about that overall process, but momentum alone is and should be terrifying.

Siegel: I’ve tried to describe momentum like this: You look at what stocks have gone up, and you buy them because you’re betting that other people are looking at the same data and that they’re also going to buy them. Obviously, there has to be a point where that game is over.

Asness: There really doesn’t have to be, Larry. One of the themes of this talk is that people can keep doing stupid things way longer than we ever thought they could.

There are two main explanations for momentum, and they’re amusingly opposite. One is your version, which is essentially overreaction: You’re buying something because it has gone up. You are using no fundamental knowledge whatsoever. The other is underreaction. Yes, you can laugh at finance when it has two competing theories that start with the opposite word. Underreaction is very simple: Fundamentals move, and so do prices, but they don’t move enough. You would expect this latter effect from the anchoring phenomenon in behavioral finance.

My personal view: It’s very hard to disentangle these explanations because I think both are true and one or the other dominates at different points in time. I know that, on this panel, it’s controversial to say this, but I think this is a very bubble-ish time. The overreaction version of momentum is dominating. In more normal times, with more typical value spreads and nothing too crazy, momentum makes a lot of its money because people don’t react enough, particularly when changes in fundamentals are revealed.

Momentum even changes your philosophical view of markets because overreaction is a disequilibrium strategy. And to the extent any of us care about whether we’re helping the world, if momentum is overreaction, then momentum investing is hurting the world. It is moving prices further away from fair value than they already are. On the other hand, if momentum is underreaction, then momentum investing is fixing an inefficiency caused by people not reacting early enough; it moves prices toward fair value, toward equilibrium.

One of my holy grails is to disentangle this question. When is one effect driving momentum, and when is the other? And I would like to be of practical use, which we all know is not always the same as disentangling it successfully.

Roger G. Ibbotson: Some people have tried to explain momentum as if it were consistent with efficient markets, although I think that’s a stretch. But it’s overreaction or underreaction. The market cannot be completely efficient if you can make money with momentum trading.

Asness: Yes, I’ve heard all the efficient-market explanations for momentum. I’m fine with it either way. As I’ve said many times, I don’t care if our premiums are risk premiums or behavioral premiums. I’ve just never bought the efficient-market explanations. There are a few. One of them is really bad and is still brought up. It’s that momentum is an estimate of the expected return. Eleven or 12 months of returns are the return people expect. So, of course, on average, it should predict. I studied this as part of my dissertation. I showed both analytically and through simulations that it does predict, but you get a 0.2 t-statistic over 100 years.

Estimates of the expected return based on one year of historical data are incredibly noisy. Then you have to ask why you are using one instead of five years, because five-year returns have a reversal aspect to them and should lead to a better estimate. Other explanations are a little bit more philosophical — they use real option theory to say that the NASDAQ was fairly priced at 5000 in the year 2000. Perhaps there were states of the world where the NASDAQ was really worth 25,000! This explanation says that momentum wasn’t irrational; it just didn’t pay off because the stocks turned out not to be worth those prices. But there was a chance. I’ll never say the chance was zero because we’re all statisticians on this forum and we’d all recoil from giving 0% or 100% odds to anything. We don’t issue guarantees. But I come fairly close to guaranteeing that the tech bubble was net irrational. It got Amazon right.

Siegel: Are we going back to discussing bubbles? If so, I have some observations. The tech bubble has been like every other bubble. It’s rational to expect one company to win and all the others to go away. We just don’t know which company the winner will be. We had 2,000 automobile companies in the early part of the 20th century. Now, we have two and a half in the United States. I can’t decide if Chrysler is a domestic or a foreign company. After the automotive bubble, we had bubbles in aviation and radio; then, in the 1960s, the electronics boom; and various others later on. You can always look back and say that the bubble was justified because of one great company that is still prospering, like IBM or Boeing. But did you want to hold the index of that industry? Probably not.

Arnott: One of the things that we did a few years back was to try to come up with a definition of the term “bubble” that could actually be used in real time. Cliff, having written Bubble Logic, would probably be very sympathetic to this effort. What we came up with is this: If you’re using a valuation model, such as a discounted cash flow (DCF) model, you’d have to make implausible assumptions — not impossible assumptions, but implausible ones — to justify current prices. And as a cross-check on that first part of the definition, the marginal buyer has zero interest in valuation models.

To apply this method to Apple, you’d have to use aggressive assumptions but not implausible ones. So, it’s not a bubble. To apply it to Tesla: I debated Cathie Wood at a Morningstar conference, and I asked what her sell discipline was, and she said, “We have a target price of $3,000. You get there if you assume 89% growth over the next five years and valuation pari passu with today’s FAANG stocks at the end of the five years.” And I had to grant that her analysis was mathematically correct.

What I didn’t say, because I had been told by my host to play nice, was, “Gosh — 89% [compounded] for five years is 25-fold growth. Do you really think that Tesla will be 25 times its current size in five years? Amazon grew to 14 times the size it was 10 years ago, and that company is a stupendous growth story.”

So, you can use a technique in real time to gauge a bubble. Where it gets really squishy is that you can’t use it to value bitcoin. But you couldn’t use it to value the US dollar either.

William N. Goetzmann: So, Rob, I’m going to show you something.

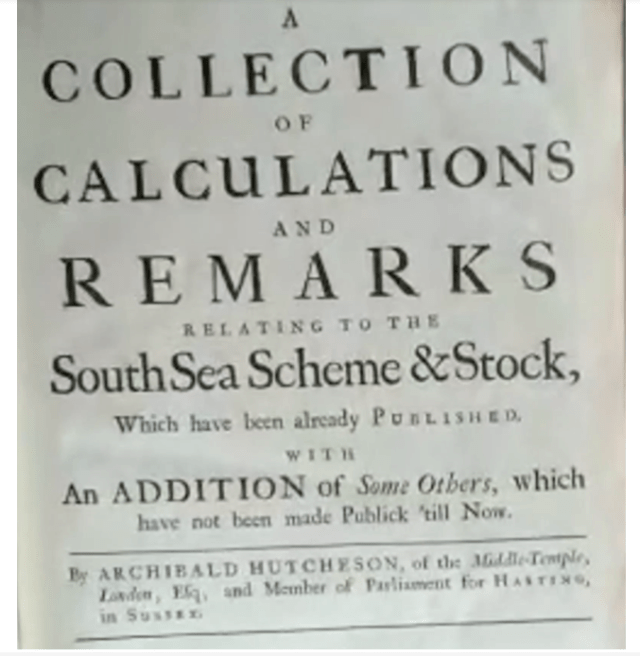

Title Page of South Sea Bubble Pamphlet from 1720

This is a book, or pamphlet, published by Archibald Hutcheson in 1720 during the South Sea Bubble. Your strategy is exactly the strategy he took. He said, “What assumptions do you have to make about the South Sea Company’s profits in order to justify the price levels of that company’s stock?” I think you just followed the footsteps of somebody who called that particular bubble before it burst.

Arnott: That’s pretty good.

Ibbotson: In the Louisiana Purchase, they actually did achieve the profits needed to justify the bubble price of the Mississippi Company. It’s just that shares in the company didn’t provide the ownership rights to them.

Arnott: The implausible part of the definition leaves room for the exception that proves the rule. Amazon wasn’t bubbling to new highs in 2000. It was cratering after 1999, but it was trading at crazy multiples even so. If you asked in 2000 what assumptions would justify the then-current price, you would have said that those assumptions aren’t plausible. Well, guess what? They exceeded it. They’re the only one.

Asness: To be interesting, any of these conversations has to be about a portfolio. There may be individual stocks that I would say are ridiculous, but you can never feel nearly as strongly about one stock as about a portfolio. One company could invent the cure for male-pattern baldness or figure out how not to fog up your glasses when you’re wearing a COVID mask. These are the two most lucrative possible inventions. The exception, clearly, should not drive the rule.

For more on this subject, check out Rethinking the Equity Risk Premium from the CFA Institute Research Foundation.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

Image credit: ©Getty Images/nikkytok

Professional Learning for CFA Institute Members

CFA Institute members are empowered to self-determine and self-report professional learning (PL) credits earned, including content on Enterprising Investor. Members can record credits easily using their online PL tracker.

[ad_2]

Image and article originally from blogs.cfainstitute.org. Read the original article here.